By Karen, on November 27th, 2010

Guardian Angels Guardian Angels

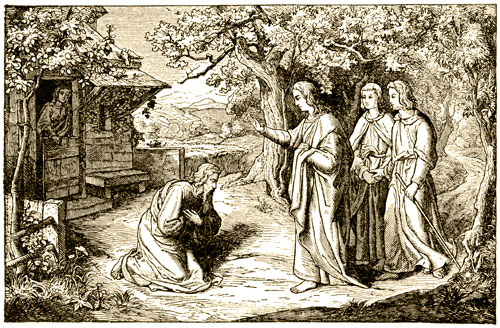

The Angel of Peace by Wilhem von Kaulbach

From the classification of the angelic hosts by the early theologians, and the special duties assigned to each class, we learn that the word angels, as ordinarily used, refers to archangels and angels only; these two classes are associated with human life in all its phases, while princedoms protect monarchies, thrones sustain the throne of God, cherubs continually worship, and seraphs adore the Most High. A belief in guardian angels those especially devoted to the care of individuals is far more widespread than the realism of the present day is inclined to admit. The godly man has a sure warrant for this trust in the ninety-first psalm:

Because thou hast made the Lord, which is my refuge, even the Most High, thy habitation; there shall no evil befall thee, neither shall any plague come nigh thy dwelling. For he shall give his angels charge over thee, to keep thee in all thy ways.

We cannot think of angels as a reality in the winged, human forms that have been given them in Art, any more than we can look for mermaids to rise from the waters mentioned in the charming legends in which these maidens acted their parts. These imaginary and apparently palpable angels are but allegories, which long have been and continue to be the angels of Art, and we could not willingly give them up. We know that they are impossible, even fantastic, if we permit ourselves to be matter-of-fact; but as emblems of spiritual guardians, sent to mortals by an ever-watchful Father, we love them; and we wish to believe in guardian angels for those who are dear to us, even if we cannot realize them for ourselves.

In one of the early councils of the Church the form of angels was considered, and it was maintained by John of Thessalonica that they were in shape like men, and should be thus represented. This decision is supported by the supposition that God spoke to the angels when he said, “Let us make man after our image;” and again by Daniel, when he describes his heavenly visitors as “like unto the similitude of the sons of men.”

A guardian angel must be ever beside his charge from the beginning to the end of life, not only to guard from evil, but also to incite to good. In sorrow he is a comforter; in weakness, strength; even in death he is faithful, and contends against the evil spirits who fight for the possession of every soul; and after death he bears the spirit to St. Michael, the Lord of Souls. Thus is the guardian angel represented in Art, as is seen in above in the illustration called The Angel of Peace.

When we observe a beautiful, unselfish life that rises far above its surroundings, we recall the belief in angelic guardians, and the description which Milton gave of a chaste, saintly soul:

A thousand liveried angels lackey her,

Driving far off each thing of sin and guilt;

And in clear dream and solemn vision

Tell her of things that no gross ear can hear,

Till oft converse with heavenly habitants

Begin to cast a beam on the outward shape.

The impersonality of angels is one of their most precious qualities. An angel is never active except as the agent of the Almighty, deputed to manifest his mercy and love to the pious, or to inflict his punishments on the wicked. Thus angels must be perfect beings; and while they love to serve, their service is void of the personality which is inherent in all human service. When they sing together it is because some good has come to men, and when they mourn it is for human affliction.

According to the teaching of the Fathers of the Church to which we have referred, the combat between good and evil angels is unceasing, and they also warrant Christians in invoking the aid of angels, and believing them to be ever near to prevent evil and encourage good. From the views of the early theologians the artists evolved their manner of representing the hosts of heaven, and while for a time angels were represented as colossal, gradually they became more graceful and lovely, as well as more human.

An ideal, a thought, must be personified to be represented to the eye, and I doubt if any new personification of angels could satisfactorily replace that which has been developed in Art during sixteen centuries, and to which we are accustomed from our earliest childhood. The angels that are known in pictures, watching over children, preventing harm to individuals, as in the sacrifice of Isaac, encouraging or even compelling worthy action, as in the case of Balaam, are dear to the heart of the world.

Guardian Angel Pictures

Guardian Angel by Bartolome Esteban Murillo

The representations of guardian angels in the more homely relations, watching sleeping infants, guiding their feeble steps, as is seen in the image above, and shielding them from accidents, are modern. To the end of the sixteenth century guardian angels, while engaged in all these minor duties, according to the teaching of the Church, were only represented in Art as performing solemn and superhuman deeds.

This may have resulted from the fixed belief of the old artists in these angelic beings, and their deep reverence for them, while modern artists are simply seeking a graceful and poetic subject. But, be this as it may, the angels who perform miracles to prevent the torture of Christian martyrs and other superhuman acts, are as essentially guardian angels as are those bending over cradles and gathering blossoms for children in the fields.

Source: Clement, Clara Erskine. Angels in Art. Boston: L. C. Page and Company, 1898.

You can discover more images of Guardian Angels at Christian Image Source.

By Karen, on November 24th, 2010

Angel Pictures

There have been many curious conceits introduced into some of the early religious pictures, and two instances in which little seraphim and angels are perched on trees, near the Virgin and Holy Child. The idea seems to be that these “Birds of God” — as Dante calls the angels — are making music and singing for the Divine Infant, some of them also praying for his solace.

Occasionally a series of pictures called the Acts of the Holy Angels has been painted. It consists of eleven strictly Scriptural subjects, usually as follows, but varied in some instances by the introduction of other motives of the same character, as, for example, the angel appearing to Hagar and to Elijah:

I. The Fall of Lucifer.

II. The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden.

III. The Visit of Three Angels to Abraham.

IV. The Angel Preventing the Sacrifice of Isaac.

V. The Angel Wrestling with Jacob.

VI. Jacob’s Dream.

VII. The Deliverance of the Three Children from the Fiery Furnace.

VIII. The Angel Slays the Host of Sennacherib.

IX. The Angel Protects Tobias.

X. The Punishment of Heliodorus.

XI. The Annunciation to the Virgin.

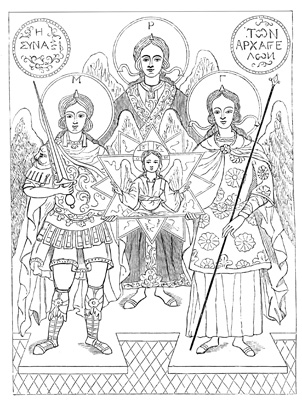

The Angelic Council - Easter Orthodox church icon of the Seven Archangels

Of the seven archangels to whom Milton refers, when he says:

The Seven

Who in God’s presence, nearest to his throne.

Stand ready at command.

only three are recognized by the Christian Church; and when three archangels are seen together, they are Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael. In the Greek Church this representation is regarded as typical of the military, civil, and religious power, and, accordingly, the costumes indicate a soldier, a prince, and a priest.

Madonna of the Rocks by Leonardo da Vinci with Uriel in the red robe

But Uriel has not been entirely ignored, even by the Christian Church, and an early tradition teaches that this archangel, and not Christ, accompanied the two disciples on their way to Emmaus. In the book of Esdras we read, “The angel that was sent unto me, whose name was Uriel.” His office was that of interpreter of judgments and prophecies, which Milton recognizes thus:

Uriel, for thou of those Seven Spirits that stand

In sight of God’s high throne, gloriously bright,

The first art wont his great authentic will

Interpreter through highest heaven to bring.

The Cathedral Monreale photographed by Jerzy Strzelecki

In several ancient churches four archangels are represented in the architectural decoration. An example in which they are very splendid is that in the mosaics above the choir arch in the Cathedral of Monreale, Palermo. These colossal, armed figures are impressive, not only from their size, but also because of their apparent realization of their illustrious rank in the order of created beings.

More frequently the four archangels are so represented as to appear to sustain the roof, or vault, in churches where the figure of Christ, or his symbol, the Lamb, is pictured as the central decoration. These are clearly intended to personate the four “who sustain the throne of God.” Their symbols are sceptres or lances; at times they stand erect, like faithful, watchful guardians; again with arms outstretched they seem to uphold the vault on which Christ is portrayed.

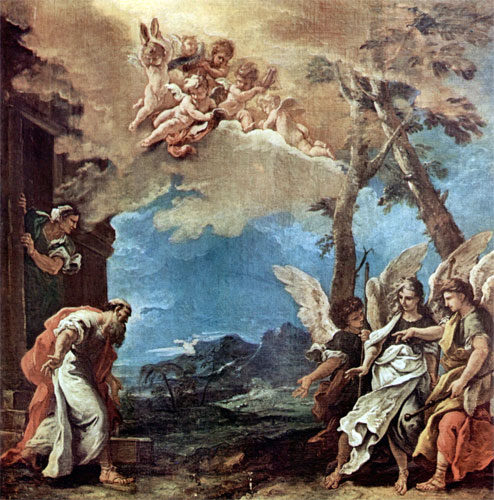

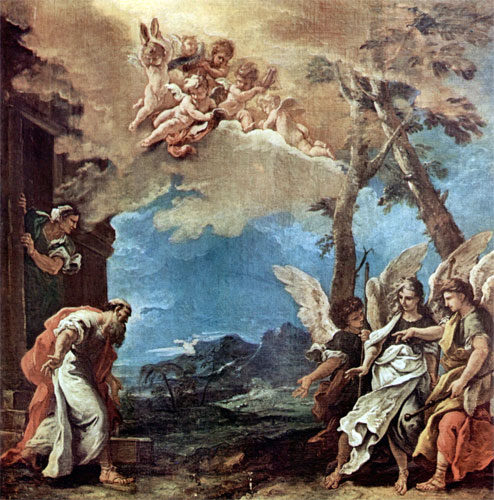

Abraham and the Three Angels by Sebastiano Ricci

The representations of three archangels are more numerous than the above, and are variously treated. In some ancient pictures they have no wings, and appear like men of princely rank and noble character. The visitors of Abraham are often thus represented, which accords with thevHebrew idea of angels at the period when Abraham was thus honored; for it was not until after the captivity, when the Egyptian custom of giving wings to their representations of messengers had been observed, that the cherubim and seraphim covered the mercy-seat with their wings.

Prophet Abraham and the Three Angels

One of the best known and most beautiful pictures of these angelic visitors is that by Raphael in the fourth arcade of the Loggie of the Vatican, which is shown as an engraving in the image above.

Source: Clement, Clara Erskine. Angels in Art. Boston: L. C. Page and Company, 1898.

You can find many more Angel Pictures at Christian Image Source.

By Karen, on November 18th, 2010

Santa Eufemia, Verona – Interior

Raphael is frequently represented without wings when leading Tobias, who — in order to emphasize the contrast between an angel and a mortal — is made very small, and is thus manifestly out of keeping with the story. When the wings appear there is no reason for dwarfing Tobias, and the picture is far more satisfactory. It is not difficult to discern that if the story of Tobias is considered as an allegory, the young man personates the Christian, guided and guarded through life by God’s mercy.

There is, in Verona, in the Church of St. Euphemia, a most impressive chapel which was decorated with pictures illustrating the story of Tobias, by Giovanni Francesco Caroto, a pupil of Mantegna, who seems to have painted more in the manner of Leonardo than in that of his master.

Various incidents of the story are effectively pictured, but the famous altar-piece, the greatest work by Caroto, is the most important of the number. It represents the Archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, — three exquisite wingless figures, — the latter being in the centre, and the only one having an aureole. He is leading Tobias, and looking down at the youth with an expression of tenderness.

St. Michael is on the right; one hand rests on his great sword, while with the other he lifts his crimson robe. His countenance, serious and indomitable in expression, fitly indicates the characteristics that his titles imply. He is the Lord of Souls and the Angel of Judgment, so far as human imagination can picture so exalted a celestial being.

St. Gabriel, on the left, holding a lily, and gazing heavenward in adoration, is a beautiful, angelic figure, far less powerful than the other archangels, and quite in harmony with his office.

The impression made by this picture, is that Gabriel realizes that his blessed office has been fulfilled, his active work is done, and adoration is now his duty and his joy; but Michael and Raphael have still their great missions to perfect ; they are still battling against evil, and guiding men in the paths of righteousness.

Caroto was a native of Verona, and his pictures are rarely seen elsewhere. His color is warm and well blended, while his drawing is severe. It is said that he was but twenty-five years old when he decorated the Chapel of St. Raphael, in 1495. He was of a quick wit, and when told that the legs of his angels were too slender, he instantly replied, ” Then they will fly the easier.”

Guardian Angels

Tobias and the three Archangels

by Sandro Botticelli

The Archangel Raphael

from a picture of Tobias and the three Archangels

by Sandro Botticelli

A very famous and wonderful picture of the three archangels with Tobias, by Botticelli, is in the Academy of Florence. The angels of this artist are frequently criticized for a certain stiffness, but their beautiful faces more than redeem any fault in their figures, and have a sweetness and depth of expression that appeals to the heart and makes one forget less important details.

Archangel Raphael and Tobias by Titian

A picture of St. Raphael leading Tobias, in the Church of St. Marziale in Venice, is said to be the earliest remaining work by Titian. For this reason it is most interesting, but it is certainly not so beautiful as that of Caroto, nor as that of Raphael, called the Madonna del Pesce, — the Madonna of the Fish, — in the Madrid Gallery, in which the master pictures the archangel whose name he bore.

Madonna del Pesce (Madonna of the Fish) by Raphael

Of this last picture Passavant says, “Here Christian poetry has found its highest expression; for it is poetry which touches all nations the most deeply, and beauty alone can give an idea of divinity.”

In the famous Madonna del Pesce, the Virgin is seated on a throne with the child; the young Tobias, holding a fish in his hand, and led by the Archangel Raphael, comes to implore Jesus to cure his father’s blindness. The Infant Saviour looks at Tobias, while his hand is on an open book which St. Jerome holds before him; the symbolic lion crouches at the feet of the saint. The background of the picture is principally formed by a curtain, but on the right a small opening of sky is seen.

The whole picture is executed in the best style of the artist’s mature power, while it is full of the fervent piety of his earlier works. The Virgin is the ideal of purity and loveliness ; the child is radiant with divine beauty ; the angel is celestial in his bearing and his countenance, while the head of the reverend saint is grand and noble in expression.

Raphael’s Madonnas sometimes seem to be but simple domestic women, gifted with beauty; in them no trace of a mystical or spiritual nature appears; but the Madonna del Pesce, like the Madonna di San Sisto, and the Madonna di Fuligno, justifies the eulogy of Vasari, when he says, “Raphael has shown all the beauty which can be imagined in the expression of a Virgin; in the eyes there is modesty, on the brow there shines honor, the nose is of a very graceful character, the mouth betokens sweetness and excellence.” The color of the Madonna del Pesce is admirably clear and harmonious, even for this great master.

This Madonna was originally painted for the Church of San Domenico Maggiore, at Naples, in which church a chapel had been erected as an especial place of worship for the numerous Neapolitans who suffer from diseases of the eye; it was not, however, permitted to serve its intended purpose, and has had an interesting history.

It is said that the Duke of Medina, when Viceroy of Naples, took the pic- ture from the Dominicans without the consent of the government, and when the prior complained to the Pope,

Medina had him escorted to the frontier by fifty horsemen, and expelled from the kingdom. In 1644 the Duke took the Virgin with the Fish to Spain, and Philip IV. placed it in the Escurial. In 18 13, when the French were compelled to leave Spain, they took this picture, with many others, to Paris.

It was painted on a panel and was in bad condition, and Bonnemaison was commissioned to transfer it to canvas. This work was not completed in 1815, when other pictures which had been taken from Spain were returned, and this Madonna remained in France until 1822. Naturally, it must have lost something of its original excellence, but it still holds a place of honor in the wonderful Italian Gallery of the Madrid Museum; it is a rival of the famous Dresden Madonna — di San Sisto — in the regard of many connoisseurs in art.

Archangel Raphael Leaving Tobias by Rembrandt

The various scenes from the story of Raphael and Tobias have been represented in the works of artists of all nations. Rembrandt four times painted the parting of Tobias from his father and mother, and several other incidents in the story. His picture in the Louvre, of the departure of the Archangel, is remarkable for its spirited action. As the angel ascends, flying through the air, he seems to part the clouds as a strong swimmer passes through the breakers of the sea.

Source: Clement, Clara Erskine. Angels in Art. Boston: L. C. Page and Company, 1898.

You can find more images of Christian Angels at Christian Image Source.

By Karen, on November 16th, 2010

Archangel Raphael Archangel Raphael

The Archangel Raphael is esteemed as the guardian angel of the human race. He especially protects the young and innocent, and guards pilgrims and travelers from harm. It was he who warned Adam of the danger of sin, and declared to him its dread consequences. Milton thus interprets the message:

Be strong, live happy, and love ! but first of all

Him, whom to love is to obey, and keep

His great command; take heed lest passion sway

Thy judgment to do aught, which else free-will

Would not admit; thine, and of all thy sons

The weal or woe in thee is placed ; beware !

That Raphael’s language was benevolent and sympathetic, as imagined by the poet, appears in Adam’s farewell to the angel:

Since to part

Go, heavenly guest, ethereal messenger.

Sent from whose sovereign goodness I adore !

Gentle to me, and affable hath been

Thy condescension, and shall be honor’d ever

With grateful memory. Thou to mankind

Be good and friendly still, and oft return!

Representations of St. Raphael are far less numerous than are those of St. Michael and St. Gabriel. They are always pleasing, and present him as a benign, sympathetic, and companionable friend to those whom he serves. His symbol is habitually a pilgrim’s staff; as a guardian hewears a sword, and has a small casket or vase, containing the “fishy charm” against evil spirits. He wears a pilgrim’s dress, has sandals on his feet, and a pilgrim bottle or wallet hangs from his belt. His flowing hair is bound by a diadem, and his beautiful face expresses the benevolence of his character and mission.

Many chapels and some churches are dedicated to the Archangel Raphael, as the chief of celestial guardians, and in these are numerous pictures commemorating his benevolent deeds. The greater part of the representations of this archangel are so connected with the history of Tobias, that it is necessary to know his story, in order to enjoy or understand these pictures. I will give this beautiful Hebrew narrative as concisely as possible:

Tobit was a rich man, and just; and he and his wife, Sara, were carried into captivity by the Assyrians. He gave alms to all his people, lived justly, and ate not the bread of the Gentiles. His misfortunes, however, increased; he had but his wife and his son, Tobias, left to him, when he became blind, and prayed for death.

At the same time a man named Raguel, who dwelt in Ecbatane, was afflicted with a daughter who was persecuted by an evil spirit. She had married seven husbands, and each one had been killed by the fiend, as soon as he entered the bridal chamber. The maiden was accused of these murders, and, like Tobit, she prayed for death.

God then sent the Archangel Raphael to cure the blindness of Tobit, and take away the reproach of the unhappy daughter of Raguel of Ecbatane.

At this time Tobit desired his son, Tobias, to go to Gabael in Media to receive ten talents, which Tobit had left in trust with Gabael. Tobias asked, “How can I receive the money, seeing I know him not ?”

Tobit gave Tobias the handwriting, and bade him seek a guide for his journey. Raphael then offered to guide the young man, who knew not that he spoke with an archangel. Tobias led Raphael to his father, and they agreed upon the wages the guide should receive, and Tobit gave directions concerning the journey, while he and Sara, his wife, were greatly afflicted at parting with Tobias.

At evening the travellers came to the river Tigris, and when Tobias went to bathe, a fish leapt out at him. Raphael told the youth to take out the liver and gall of the fish and preserve it carefully, which being done, they roasted the fish and ate it. When Tobias asked why he should keep the liver and the gall, the angel told him that the heart and liver would cure a person vexed with an evil spirit, if a smoke from them was made before the person; and the gall would cure the blindness of one afflicted with whiteness of the eyes.

The Archangel Rapahel Conducting the Young Tobias by Andrea del Sarto The Archangel Rapahel Conducting the Young Tobias by Andrea del Sarto

In our illustration from the picture by Andrea del Sarto, in the Belvedere, Vienna, Tobias carries the fish, and it appears to represent the moment when Raphael is making his explanation of its purpose.

As they proceeded Raphael said, “Brother, to-day we shall lodge with Raguel, who is thy cousin; he hath but one daughter, named Sara; I will ask her as a wife for thee: she belongs to thee by law, and is fair and wise, and you can marry her when we return.” Then Tobias, who knew the fate of the seven husbands, was filled with fear lest he too should die, and thus afflict his parents, who had no other child.

But Raphael assured Tobias that Sara was the wife that the Lord intended for him, and that when he entered the marriage chamber the evil spirit would flee at the smoke he should make with the liver of the fish, and would never return. When Tobias heard this he loved the maiden, and his heart was effectually joined to her.

When they came near Ecbatane, they met Sara, and she led them to her parents, who rejoiced to see them, and wept when they heard of the blindness of Tobit. While the servants of Raguel prepared a supper, Tobias said to the angel, “Speak of those things of which thou didst talk, and let this business be dispatched.” Then Raphael asked Raguel to give Sara to Tobias; but the father was sore distressed, and told of the death of the seven who had already married her; but as Sara belonged to Tobias by the law of Moses, his request could not be denied, and before they did eat together, Raguel joined their hands, and blessed them.

Then the marriage chamber was prepared, and the maiden wept; but her mother comforted her, and when Tobias entered and made the smoke as the angel had directed, the evil spirit fled. Tobias and Sara knelt in thankfulness, and Tobias prayed as Raphael had told him, and Sara said, “Amen.”

In the morning Raguel dug a grave, for he wished to bury Tobias quickly, that no one should know what had happened; but when he sent to see if he were dead, it was found that the young husband was quietly sleeping. Then there was great rejoicing, and a wedding feast was made, which lasted fourteen days. Meanwhile, Raphael went to Gabael and received from him the ten talents, and when the feast ended, the angel conducted Tobias and Sara to Tobit, and Raguel bestowed on Sara half his wealth.

As they approached Nineveh, Raphael said to Tobias, “Let us haste before thy wife, to prepare the house: and take thou the gall of the fish.” The mother of Tobias was watching for his return, and was greatly alarmed at his long absence. When she saw him with his guide, and the little dog which he had taken away, she ran to Tobit with the news, and they rejoiced greatly. Raphael now said to Tobias, “I know that thy father will open his eyes; therefore anoint them with the gall, and being pricked therewith, he shall rub them, and the whiteness shall fall away, and he shall see thee.” And so it was, and Tobit was blind no more, and they all rejoiced and blessed God.

Then Tobias recounted all that had happened, and his parents went out with him to meet his wife, and her servants, and cattle, and all she had brought with her. And the people were filled with wonder to see that Tobit was blind no more, and they rejoiced greatly with him during seven days when he kept a feast.

Tobit bade his son to call his guide and give him more than the wages that had been named. And Tobias wished to give the angel half of all he had brought back with him, and Tobit said, “It is due unto him.” But when Raphael knew their intentions he commanded them to glorify God for all his goodness, and told Tobit that his goodness and sorrows and those of the daughter of Raguel had been known in heaven, and God had sent him to heal all these troubles, and added, “I am Raphael, one of the seven holy angels, which present the prayers of the saints, and go in and out before the glory of the Holy One.”

The Archangel Raphael Refusing the Gifts of Tobias by Giovanni Biliverti

The illustration after the picture of Giovanni Biliverti in the Pitti Gallery, Florence, places before us the scene, when, refusing reward, the Archangel declared himself. The beauty of the angel, the affectionate enthusiasm of Tobias, and the sincere and reverent gratitude of the old Tobit are wonderfully portrayed, while the young wife and the aged mother in the background complete the group of those who have been delivered from their sorrows by the messenger of the Most High.

From the time when the angel left them Tobit and Raguel prospered, and after Tobit and Sara died, Tobias removed to Ecbatane and inherited the wealth of Raguel; he lived with honor to be an hundred and seven and twenty years old, and to hear of the destruction of Nineveh.

Milton thus refers to the story of Tobias:

The affable archangel

Raphael; the sociable spirit that design’d

To travel with Tobias, and secured

His marriage with the seven times wedded maid.

Source: Clement, Clara Erskine. Angels in Art. Boston: L. C. Page and Company, 1898.

You can find more images of the Archangel Raphael at Christian Image Source.

By Karen, on November 14th, 2010

St. Michael at the Castle of San’ Angelo, Rome

by Matthias Kabel

In the legends of St. Michael we read that in the sixth century, when the plague was raging in Rome, and processions threaded the streets chanting the service since known as the Great Litanies, the Archangel Michael appeared, hovering over the city. He alighted on the summit of the Mausoleum of Hadrian and sheathed his sword, from which blood was dripping. From that hour the plague was stayed, and from that day the Mausoleum, which is surmounted by a statue of the Archangel, has been called the Castle of Sant’ Angelo.

The legends also give an account of two appearances of St. Michael when he commanded the erection of churches—one at Monte Galgano, on the east coast of Italy, and the second at Avranches in Normandy. The first site was found to cover a wonderful stream of water, which cured many diseases, and made the church of Monte Galgano a much frequented place of pilgrimage.

The church in Normandy is on the celebrated Mont Saint Michael, and is famous in all Christian countries. From the time when the angel appeared to St. Aubert, the bishop, and commanded him

to build the church, this saint was greatly venerated in France, and was made patron of France and of the order which St. Louis instituted in his honor.

The first church erected in England was small, but Richard of Normandy and William the Conqueror raised a magnificent abbey, which overlooked the most picturesque scenery, and for this reason, if no other, remains a much frequented spot

The old English coin called an angel was so named from the representation of St. Michael which was stamped upon it.

Announcement of the Death of the Virgin Mary by Fra Filippo Lippi Announcement of the Death of the Virgin Mary by Fra Filippo Lippi

The pictures of St Michael announcing to the Virgin Mary the time of her death, bear so strong a resemblance to those of the Annunciation, that it is necessary to remember that these have the

symbols of a palm on a lighted taper in the hand of the angel, instead of the lily of the Archangel Gabriel, as is seen in our illustration of a beautiful picture in the Florentine Academy.

The legend relates that on a certain day the heart of Mary was filled with an inexpressible longing to see her Son, and she wept sorely, when an angel clothed in light appeared before her, saluting her, and saying, “Hail, O Mary! Blessed by Him who hath given salvation to Israel! I bring thee here a branch of palm gathered in paradise; command that it be carried before thy bier in the day of thy death, for in three days thy soul shall leave thy body, and thou shalt enter into paradise where thy Son awaits thy coming.”

Mary answering, said, “If I have found grace in thy sight tell me thy name, and grant that the Apostles may be reunited to me, that in their presence I may give up my soul to God. Also, I pray thee, that after death my soul may not be affrighted by any spirit of darkness, nor any evil angel be given power over me.”

And the archangel replied, “My name is the Great and Wonderful. Doubt not that the Apostles shall be with thee to-day, for he who transported the prophet Habakkuk by the hair of his head to the lions’ den, can also bring hither the Apostles. Fear thou not the evil spirit, for thou hast bruised his head, and destroyed his kingdom.” And the angel departed, and the palm branch shed light from every leaf and sparkled as the stars of heaven.

And the duty of the archangel was thus fulfilled until he should again appear as Lord of Souls to receive the spirit of the Virgin, to guard it until it should again inhabit her sinless body.

Source: Clement, Clara Erskine. Angels in Art. Boston: L. C. Page and Company, 1898.

You can find free Archangel Art at Christian Image Source.

By Karen, on October 30th, 2010

Archangel Michael Archangel Michael

The representations of St. Michael as the Lord of Souls are less numerous than those of the subjects mentioned in Part 1, but are very interesting. In some votive pictures he appears as the protector of those who have struggled with evil, and gained a victory. In such pictures the angel has his foot upon the dragon, or holds a dragon’s head in his hand, and bears the banner of victory.

Again, Michael is represented with his scales engaged in weighing the souls of the dead; in such pictures he is unarmed, and bears a sceptre ending in a cross. The souls are typified by little naked human figures; the accepted spirits usually kneel in the scales, with hands clasped as in prayer; the attitude of the rejected souls expresses horror and agony, which is sometimes emphasized by the figure of a demon, impatient for his prey, who reaches out his talons, or his devil’s fork, to seize the doomed spirits.

Archangel Michael as the Lord of Souls from The Last Judgment Archangel Michael as the Lord of Souls from The Last Judgment

by Rogier van der Weden

Leonardo da Vinci represented the angel as presenting the balance to the Infant Jesus, who has the air of blessing the pious soul in the upper scale. Signorelli, about 1500, painted a picture of this subject, which is in the church of San Gregorio at Rome, in which the archangel, in a suit of mail, stands with his wings spread out, and the balance with full scales held above a fierce, open-mouthed dragon. The lance of the archangel has pierced through the under jaw of the beast and entered his body, making an ugly wound, and a hideous little demon, resting on his tiny black wings, is clutching the condemned spirits in the lower scale.

In pictures of the Assumption or Glorification of the Virgin, if St. Michael is present, it is in his office of Lord of Souls, as the legends of the Madonna teach that he received her spirit, and guarded it until it was again united with her sinless form.

The Translation of St. Catherine of Alexandria The Translation of St. Catherine of Alexandria

by Heinrich Mucke

As Lord of Souls it is taught that St. Michael conducted the spirits of the just to heaven, and even cared for their bodies in some instances. The legend of St. Catherine of Alexandria teaches that her body was borne by angels over the desert and sea to the top of Mount Sinai, where it was buried, and later a monastery was built over her sepulchre. In the picture of the Translation of St. Catherine, shown above, St. Michael is one of the four celestial bearers of the martyr saint.

In rare instances St Michael was represented without wings. Such a figure standing on a dragon is a St. George, unless the balance is introduced. When the archangel stands upon the dragon with the balance in his hand, he appears in his double office as Conqueror of Satan and Lord of Souls. Memorial chapels and tombs were frequently decorated with this subject, a notable instance being that on the tomb of Henry VII., in Westminster Abbey.

In pictures of the Last Judgment, St. Michael is sometimes seen in the very act of weighing souls, symbolizing those of whom St. Paul said, “We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trump: for the trumpet shall sound, and the dead shall be raised incorruptible, and we shall be changed.”

Since the Archangel Michael was made the guardian of the Hebrew nation, he was naturally an important actor in many scenes connected with their history. It was he who succored Hagar in the wilderness (Genesis xxi., 17), who appeared to restrain Abraham from the sacrifice of Isaac (Genesis xxii., 1 1). He brought the plagues on Egypt and led the Israelites on their journey. The Jews and early Christians believed that God spoke through the mouth of Michael in the Burning Bush, and by him sent the law to Moses on Mount Sinai. When Satan would have entered the body of Moses, in order to personate the prophet and deceive the Jews, it was Michael who contended with the Evil One, and buried the body in an unknown place, as is distinctly stated by Jude. Signorelli chose this as the subject of one of his frescoes in the Sistine Chapel.

Archangel Art Archangel Art

It was Michael who put blessings instead of curses into Balaam’s mouth (Numbers xxii., 35), who was with Joshua in the plain of Jericho (Joshua v., 13), who appeared to Gideon (Judges vi., 2), and delivered the three faithful Jews from the fiery furnace (Daniel iii., 25). This last subject is one of the earliest in Christian art, and was a symbol of the redemption of man by Jesus Christ. There are still other like offices which St. Michael filled as the protector of the Jews, while several important works are attributed to him in the Apochrypha and in the Legends of the Church.

For example, in the apocryphal story of Bel and the Dragon, it is related that when King Cyrus had thrown the prophet Daniel into the lions’ den, and he had been six days without food, the angel of the Lord appeared to the prophet Habakkuk in Jewry, when he had prepared a mess of potage for the reapers in his field, and the angel commanded Habakkuk to carry the potage to Babylon and give it to Daniel.

“Then Habakkuk said, ‘Lord, I never saw Babylon; neither do I know where the den is.’ Then the angel of the Lord took Habakkuk by the hair of his head, and set him in Babylon over the lions’ den, and Habakkuk cried, saying, ‘O Daniel, Daniel, take the dinner which God hath sent thee,’ and the angel again set Habakkuk in his own place.”

At one period this subject was represented on sarcophagi, but it can also be found in prints after the Flemish artist, Hemshirk.

Source: Clement, Clara Erskine. Angels in Art. Boston: L. C. Page and Company, 1898.

Find free images of Michael the Archangel at Christian Image Source.

By Karen, on October 29th, 2010

Archangel Art Archangel Art

The Archangel Michael is reverenced as the first and mightiest of all created beings. He was worshiped by the Chaldeans, and the Gnostics taught that he was the leader of the seven angels who created the universe. After the Captivity the Hebrews regarded him as all that is implied by the Prophet Daniel when he says, “Michael, the great prince which standeth for the children of thy people.” It is believed that he will be privileged to exalt the banner of the Cross on the Judgment Day, and to command the trumpet of the archangel to sound; it is on account of these offices that he is called the “Bannerer of Heaven.”

As captain of the heavenly host, it devolved on Michael to conquer Lucifer and his followers, and to expel them from heaven after their refusal to worship the Son of Man ; and terrible was the punishment he inflicted on them. Chained in mid-air, where they must remain until the Judgment Day, they behold all that happens on earth. Man, whom they disdained, has flourished in their sight, and wields a power that they may well envy, while the souls of the redeemed constantly ascend to the heaven which is closed to them. Thus are they constantly tormented by hate, and a desire for revenge, of which they must ever despair.

St. Michael is represented in art as young and severely beautiful. In the earliest pictures his drapery is always white and his wings of many colors, while his symbols, indicating that his conquests are made by spiritual force alone, are a lance terminating in a cross, or a sceptre. Later, it became the custom to represent him in a costume and with such emblems as indicated the nature of the work in which he was engaged; and except for the wings, his picture might often be mistaken for that of a celestially radiant knight, since he is clothed in armor, and bears a sword, shield, and lance. But his seraphic wings and his bearing mark him as a mighty spiritual power, and this impression is increased rather than lessened, when in all humility he is in the act of worship before the Divine Infant, or stands in reverent attitude near the Madonna, as if to guard her and her heaven-sent son.

Archangel Michael Archangel Michael

When conquering Satan the treatment is varied, but the subject is easily recognized. More frequently than otherwise, the archangel stands on the demon, who is half human and half dragon, wearing a suit of mail, and is about to pierce the evil spirit with a lance or bind him in chains.

Such pictures date from the earliest attempts in religious painting, and the same subject was represented in ancient sculpture. Some of these works are so crude as to be absurd, but for their manifest reverence and sincerity. An early sculpture in the porch of the Cathedral of Cortona, probably dating from the seventh century, presents the archangel in long, heavy robes, reaching to his feet; he stands solidly on the back of the dragon, and as if to make the footing more secure, the beast curls his tail in air and lifts his head as high as possible, holding his mouth wide open, into which St. Michael presses his lance without a struggle. The whole effect is that of some calm and commonplace occurrence, and is in striking contrast with the spirit of the conflict which is represented, as well as with the superhuman combat depicted by later artists.

The dragon is personified by a variety of horrible reptilian forms. Some artists even attempted to follow the apocalyptic description. “For their power is in their mouth, and in their tails, for their tails were like unto serpents, and had heads, and with them they do hurt.”

Lucifer is not always alone, but is sometimes surrounded by demons, who crouch with him at the feet of St. Michael, before whom a company of angels kneel in adoration.

During the sixteenth century the pictures of this archangel took on the military aspect and, but for the wings, would have represented St. George, or a Crusader of the Cross, as suitably as the great Warrior Angel.

An exquisite small picture of this type, now in the Academy at Florence, was painted by Fra Angelico. The lance and shield and the lambent flame above the brow are the only emblems; the latter symbolizing spiritual fervor. The rainbow-tinted wings are raised and fully spread, meeting above and behind the head; the armor is of a rich dark red and gold. The pose and the expression of the countenance indicate the reserved power and the godlike tranquility of the celestial warrior, and fitly represent him as the patron of the Church Militant.

The representations of St. Michael conquering Lucifer are so numerous and so interesting technically, that any adequate account of them and of their artistic and theological development would fill a volume, and might be considered rather tiresome. However, there are two examples which are very generally accepted as the most satisfactory of them all.

Archangel Michael Casting Satan out of Heaven by Raphael Archangel Michael Casting Satan out of Heaven by Raphael

The first, painted by Raphael when at his best, is in the Louvre. It was a commission from Lorenzo de Medici, who presented it to Francis I. The subject was doubtless chosen by Raphael as a compliment to the sovereign, who was the Grand Master of the Order of St. Michael, the military patron saint of France.

It was painted on wood, and sent with three other pictures, packed on mules, to Fontainebleau, where Lorenzo was visiting, in May, 1518. The picture was somewhat injured on the journey. In 1773 it was transferred to canvas, and “restored” three years later, the restorations were eventually removed. The picture has no doubt suffered from these chances and changes, but the fact remains that it is still a glorious work by a great master.

The beautiful young angel does not stand upon the fiend beneath him, but, poised in air, he lightly touches with his foot the shoulder of the demon in vulgar human form, fiery in color, having horns and a serpent’s tail. The expression of the angel is serious, calm, majestic, as he gazes down upon the writhing Satan, whose face, as he struggles to raise it, is full of malignant hate. This detail is lost in the black and white reproductions.

Michael grasps the lance with both hands, and so natural is the action, so easy and graceful, that the beholder instinctively waits to see the weapon do its work, while flames rise from the earth as if impatient to engulf the disgusting demon. The head of the angel, with its light, floating hair is against the background of the brilliant wings, in which blue, gold, and purple are gloriously mingled; his armor is gold and silver; a sword hangs by his side, and an azure scarf floats from his shoulders. His legs are bare, and his feet shod with buskins, which leave the toes uncovered. The contrast between the exquisite, angelic flesh tints, rosy in hue, and the brown coloring of the demon, effectively emphasizes the beauty of purity and the loathsomeness of evil.

The Archangel Michael Overpowering Satan by Guido Reni The Archangel Michael Overpowering Satan by Guido Reni

The St. Michael of Guido Reni so closely resembles that of Raphael in general treatment, that it is more nearly just to compare these works than is usually the case with pictures of the same subject by different masters. The attitude of Guido’s saint is like that of a dancing-master when contrasted with the pose of Raphael’s, and his demon is simply low and base, devoid of malignity or any supreme evil.

But the head and face of Guido’s Michael make his picture wonderful; they adequately express divine purity and beauty, while the studied and fictitious qualities of Guido’s art here at their best serve to enhance the exquisite effect of this angelic warrior, and the picture is justly esteemed as one of the treasures of the Cappucini at Rome.

Source: Clement, Clara Erskine. Angels in Art. Boston: L. C. Page and Company, 1898.

You can find many free images of Archangel Michael at Christian Image Source.

By Karen, on October 17th, 2010

A very ancient Annunciation, of peculiar and elaborate arrangement, dating from the fifth century, is in mosaic, over the arch in front of the choir in the church of Santa Maria Maggiore, in Rome. The classical treatment of the dresses, and of the entire composition, makes this work so different from the usual conception of the subject as to be of observation. There are two scenes: in the first, the archangel is sent on his mission, and is rapidly flying towards the earth, as if in haste to utter his joyous salutation, “Hail! thou art highly favored! Blessed art thou among women!” A very ancient Annunciation, of peculiar and elaborate arrangement, dating from the fifth century, is in mosaic, over the arch in front of the choir in the church of Santa Maria Maggiore, in Rome. The classical treatment of the dresses, and of the entire composition, makes this work so different from the usual conception of the subject as to be of observation. There are two scenes: in the first, the archangel is sent on his mission, and is rapidly flying towards the earth, as if in haste to utter his joyous salutation, “Hail! thou art highly favored! Blessed art thou among women!”

The second scene presents Gabriel standing before the Virgin, who is seated on a throne, behind which are two guardian angels. This representation is so utterly unlike what is known as Christian art as to make a lasting, impression, by reason of its classical treatment; all the details have an air of belonging to an earlier period than that known as medieval, and the figures might be those of ancient Greeks.

It is extremely curious and interesting to observe the various methods of representing the Archangel Gabriel in pictures of the Annunciation. At times he might be mistaken for the ambassador of a proud and powerful earthly potentate. He is clothed in gorgeous raiment, with a rich train, sometimes borne by one, and again by three page-like angels, while carries himself with majestic haughtiness

We do not wonder that the difference between the estate of an archangel sent by God, and the humility of the Virgin of Galilee, should have misled some artists, or that with them the angel held the first place, especially as it was only thus that any element of splendor could be introduced into their pictures. Indeed, we have engravings after a picture by Raphael, in which the Virgin is kneeling before the angel, who raises the right hand in benediction.

But the gradual increase in the veneration, accorded to the Virgin, and the title of Queen of Heaven, and Queen of Angels, which were bestowed on her, soon changed the spirit of the representations of the Annunciation; and while the Virgin loses none of her humility and submission, the angel bows, and even kneels, to her, thus emphasizing his acknowledgment of her superior holiness, since an archangel could only kneel before spiritual perfection.

It was well that the patriarchs and prophets should acknowledge the superiority of the angels sent to them, but the glory of the Mother of Christ should be represented as commanding the reverence of even the highest of created beings—only thus could the faith of the Church for which these religious pictures were painted, be fittingly illustrated.

Archangel Pictures Archangel Pictures

Thus it became customary to omit the scepter in the hand of the angel, and to give him the lily alone, or the lily and the scroll. Indeed, there are notable pictures in which Gabriel has no symbol, but with hands clasped over his breast, and head inclined, he seems to worship the Virgin while declaring his mission to her. There are, however, few Annunciations in which the lily does not appear. It is the special symbol of the purity of Mary, to whom is applied the verse from the Song of Solomon: “I am the rose of Sharon, and the lily of the valleys.” In some pictures the lily is seen in a vase near the Virgin.

Occasionally the symbol of peace is introduced in pictures of the Annunciation by placing a crown of olive on the head of the archangel, or an olive branch in his hand. Here Gabriel is presented as announcing the “Peace on earth and good will towards men,” which Raphael and his attendant angels chanted to the shepherds on the birth of Jesus.

The early German painters were fond of picturing Gabriel in priestly robes, heavily embroidered, and rich in color. This dress supplied the same gorgeous effect as was given by the princely trains. In these pictures Gabriel usually kneels, his ample robes falling on the pavement around him, thus avoiding the proud bearing of the regally vestured messenger.

The simplicity of the scene, when Gabriel is appropriately draped in the filmy white robe, which is the usual conception of an angel’s dress, is far more satisfactory and harmonious with the spirit of the miraculous Annunciation than any splendid vestments can possibly be.

The earliest pictures of the Annunciation, however, in spite of unsuitable costumes, and of certain technical imperfections, are more acceptable to the reverent mind than are those of a later time, in which the angel is scantily draped and is apparently conscious of his physical beauty, while the Virgin is entirely wanting in grace or dignity. Such a rendering of this scene is most offensive; all the more so that these pictures are frequently well executed, and were they not presented as representations of this sacred subject, but given some appropriate title, they would have claims to a certain artistic approbation.

The Annunciation by Alessandro Allori The Annunciation by Alessandro Allori

Other artists, like Allori, in the illustration above, represent an all too conscious Virgin, an angel who apparently poses for a picture, and a mass of utterly inappropriate detail. This Annunciation, which is in the Florentine Academy, affords an excellent example of this objectionable style, and its faults are emphasized when it is compared with the serious dignity of Fra Filippo’s picture and that which follows, by Fra Angelico. By such comparisons the great difference between true sentiment and affectation in Art becomes apparent.

There are some Annunciations in which the Virgin is represented as starting up from fear or surprise, quite as one might fancy that a tragedy queen would do, were her privacy unceremoniously disturbed.

Again the Virgin Mary is fainting from emotion, and thus could not have replied to the angel in the Scriptural words, “Behold the handmaid of the Lord; be it unto me according to thy word.”

Not infrequently, in representations of this scene, the Holy Spirit, as a dove, hovers above or near the Virgin, or flies in through a window; again the Almighty is seen in the clouds, surrounded by a celestial light, and sometimes attended by celestial spirits. In rare instances the Eternal Father sends the Infant Jesus down from the sky bearing a cross, and preceded by a dove. These extremely symbolic Annunciations are usually of an early date.

Fra Angelico painted the Annunciation with intense reverence and simplicity. There is an illustration of his fresco on the wall of the corridor in his convent of San Marco, in Florence, which some believe is one of the most beautiful and spiritual Annunciations in existence. It tells the sacred story faithfully; there is nothing introduced that does not essentially belong here. The Virgin gives the impression of being equal to the angel in purity and goodness; he is superior only in knowledge.

Archangel Gabriel Archangel Gabriel

Angelico believed that he was divinely directed in his work, which he began with prayer, and for this reason he would never change his original design. His care in the finish of his pictures was phenomenal; his draperies were dignified; his color and composition were harmonious. It has well been said of his works: “Every part contributed to that unity of tenderness, inspiration, and religious feeling which marks his pictures, and which are such as no one man had ever succeeded in accomplishing.”

Angelico knew nothing of human anxieties and struggles, and could not paint them; he could not depict the hatred of the enemies of Christ; martyrdoms and persecutions were feebly represented by him, but to annunciations, coronations of the Virgin, and kindred subjects he imparted a sweetness and a spiritual fervor that has rarely, if ever, been surpassed. We can imagine him rising from his prayers with his conceptions of the Virgin and the archangel as distinct in his mind’s eye as they are to our vision in his pictures, and it is easy to understand that the man who lived in his atmosphere would be void of ambition, and refuse to be made Archbishop of Florence, as he did.

Gabriel is reverenced by the Jews as the chief of the angelic guards and the keeper of the celestial treasury. The Mohammedans regard him as their patron saint; their prophet believed this archangel to be his inspiring and instructing spirit. Thus he is important in the faith and legends of Christians, Jews, and Mohammedans alike. Milton may have had the Jewish tradition in mind when he represented Gabriel as the guardian of paradise:

Betwixt these rocky pillars Gabriel sat,

Chief of the angelic awaiting night.

Source: Clement, Clara Erskine. Angels in Art. Boston: L. C. Page and Company, 1898.

Please visit Christian Image Source for more beautiful images of Archangel Art.

By Karen, on October 16th, 2010

Archangel Pictures Archangel Pictures

The Archangel Gabriel is mentioned by name but twice in the Old Testament. First in Daniel viii., 16, when he explained the vision which the prophet had seen, and again in Daniel ix., 21, when Gabriel appeared to Daniel to give him skill and understanding.

Likewise in the New Testament he is twice mentioned– in Luke i., 19 and 26, when he announced to Zacharias the birth of John the Baptist, and to the Virgin Mary that she was favored of the Lord, and blessed among women. On each of those occasions he filled the office of a messenger or bearer of important tidings. It is believed to have been Gabriel who fought with the Angel of the Kingdom of Persia for twenty-one days, when Michael came to his relief, and Gabriel again visited Daniel to strengthen him, and explain “that which is noted in the scripture of truth,” and to announce that the king of Greece should overcome the king of Persia. After which Gabriel returned to his battle with the Angel of Persia.

The contest with the angel of Persia is a subject which offers unusual opportunities in its artistic representation; it is, however, much the same in spirit as the struggle between Michael and Lucifer, and the preference was given to the latter by the painters of religious subjects.

St. Gabriel has been many times portrayed as the messenger announcing the birth of John the Baptist and that of Jesus Christ. In the apocryphal legends he also foretells the birth of Samson, and that of the Virgin Mary. From these frequently repeated messages which foretold important births, Gabriel naturally came to be regarded as the angel who presides over childbirth.

The great number of representations of the Annunciation to the Virgin Mary make it difficult to select those of which to speak. The earliest pictures of this event portray it with great simplicity, purity, and grace. A spiritual mystery is being depicted, and is handled with sincere reverence and the utmost delicacy.

The scene is usually the portico of an ecclesiastical edifice. When seated, the Virgin is on a species of throne, but she is more frequently represented as standing. The archangel is at some distance from her, not infrequently quite outside the porch. He is majestic and beautiful; is clothed in white, wearing the tunic and pallium or archbishop’s mantle. His wings are large, and brilliant with many colors, and his abundant hair is bound with a jeweled tiara. He bears either the sceptre of power or a lily in one hand, while the other is extended in benediction. Sometimes he holds a scroll inscribed with the words, “Ave Maria, gratia plena.” Hail! Mary, full of grace, the words Dante represents Gabriel as constantly repeating in paradise.

The angel is the chief figure in this scene in the earlier pictures; he is joyfully triumphant, announcing the coming of the Saviour, while the Virgin is all humility and submission; in some cases her head is covered, an extreme expression of lowliness, and she is always self-effacing in attitude and expression.

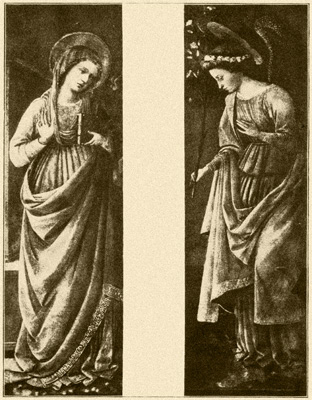

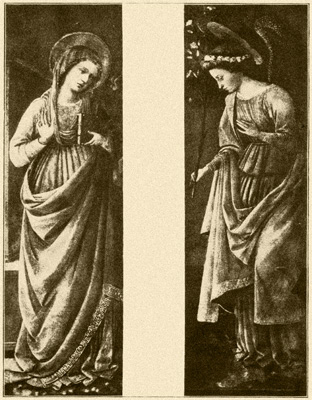

A Divided Annunciation by Fra Filippo Lippi A Divided Annunciation by Fra Filippo Lippi

An early custom in churches was to place the picture of the Virgin on one side of the altar, and that of the angel the other side; or, if both figures were in the same frame, a division was made by an architectural pillar, or a conventional ornament between them. In many cases the Virgin and the Archangel were placed separately above, or on each side of some scene from the life of Jesus, usually an altar piece. The picture by Fra Filippo Lippi, shown above, is a very fine example of the so-called “divided Annunciations.” It is in the Florentine Academy. This picture is very beautiful, and fittingly expresses the humility and surprise of the Virgin and the reverence of the heavenly messenger. It is also a good example of Fra Filippo’s style; his draperies were graceful, abundant, and usually much ornamented with signs in gold, of which we have here, enough for elegance, while it is not overdone as in other works of this artist.

Source: Clement, Clara Erskine. Angels in Art. Boston: L.C. Page and Company, 1898.

Be sure to visit Christian Image Source for more free illustrations of Archangel Gabriel.

By Karen, on October 3rd, 2010

Apse Mosaic, San Vitale, Ravenna (Flickr) / CC BY-NC 3.0 Apse Mosaic, San Vitale, Ravenna (Flickr) / CC BY-NC 3.0

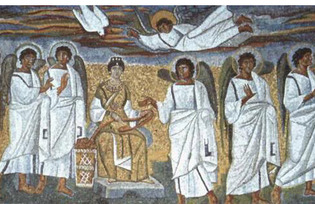

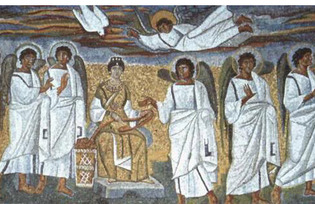

The earliest instance of the Archangels introduced by name into a work of art is in the old church of San Michele at Ravenna (A. D. 545). The mosaic in the apse exhibits Christ in the centre, bearing in one hand the cross as a trophy or sceptre, and in the other an open book on which are the words, “Qui cidef me videt et Patrem meum” [John xiv. 9]. On each side stand Michael and Gabriel, with vast wings and long scepters; their names are inscribed above, but without the Sanctus and without the Glory. It appears, therefore, that at this time, the middle of the sixth century, the title of Saint, though in use, had not been given to the Archangels.

Vault of the San Zeno Chapel, Basilica di Santa Prassede, Rome, Italy by Sixtus Vault of the San Zeno Chapel, Basilica di Santa Prassede, Rome, Italy by Sixtus

When, in the ancient churches, the figure of Christ or of the Lamb appears in a circle of glory in the centre of the roof and around, or at the four corners, four angels who sustain the circle with outstretched arms, or stand as watchers, with sceptres or lances in their hands, these are presumed to be the four Archangels “who sustain the throne of God.” Examples may be seen in San Vitale at Ravenna; in the chapel of San Zeno, in Santa Prassede at Rome; and on the roof of the choir of San Francesco d’Assisi.

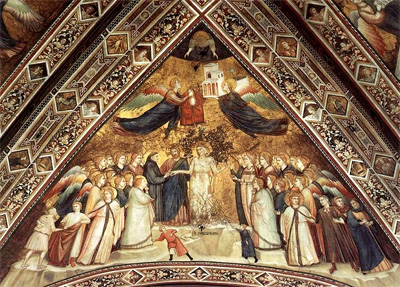

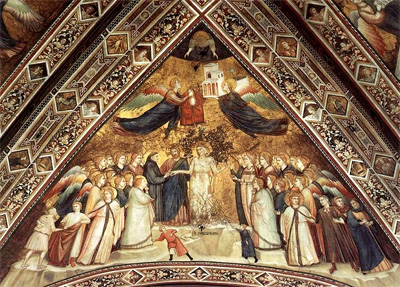

Franciscan Allegories – Allegory of Giotto di Bondone Franciscan Allegories – Allegory of Giotto di Bondone

Allegory of Poverty

c. 1330, Fresco, Lower Church, San Francesco, Assisi

So the four Archangels, stately colossal figures, winged and armed and sceptred, stand over the arch of the choir in the Cathedral of Monreale, at Palermo. (Greek mosaic, A. D. 1174.)

So the four angels stand at the four corners of the earth (Rev. vii. 1) and hold the winds, heads with puffed cheeks and dishevelled hair. (MS. of the Book of Revelation, fourteenth century, Trinity College, Dublin.)

Uriel is seldom represented by name, or alone, in any sacred edifice. In the picture of Uriel painted by Allston, he is the “Regent of the Sun,” as described by Milton, not a sacred or scriptural personage. On a shrine of carved ivory (Hotel de Cluny [Paris]) can be seen the four Archangels as keeping guard, two at each end. The three first are named, as usual, St. Michael, St. Gabriel, St. Raphael. The fourth is styled St. Cherubin–the same name inscribed over the head of the angel who expels Adam and Eve from Paradise. There is no authority for such an appellation applied individually, but in a famous legend of the Middle Ages, “La Penitence d’Adam,” the angel who guards the gates of Paradise is designated as “Lorsque l’Ange Chernbin vit arriver Seth aux portes de Paradis,” etc. The four Archangels, however, seldom occur together, except in architectural decoration.

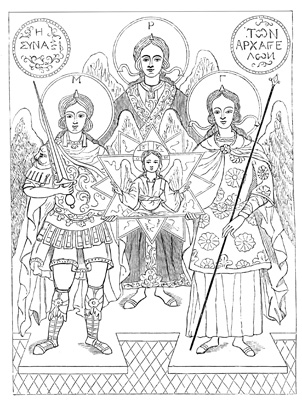

The Three Archangels from an Ancient Greek picture. The Three Archangels from an Ancient Greek picture.

On the other hand, devotional pictures of the three Archangels named in the canonical Scriptures are of frequent occurrence. They are often grouped together as patron saints or protecting spirits, or they stand round the throne of Christ, or below the glorified Virgin and Child, in an attitude of adoration. According to the Greek formula, the three in combination represent the triple power–military, civil, and religious– of the celestial hierarchy. St. Michael being dressed as a warrior, Gabriel as a prince, and Raphael as a priest. In the Greek picture shown above, the three Archangels sustain in a kind of throne the figure of the youthful Christ, here winged, as being Himself the supreme Angel and with both hands blessing the universe. The Archangel Raphael has here the place of dignity as representing the Priesthood, but in western art Michael takes precedence of the two others, and is usually placed in the center as Prince or Chief.

Source: Jameson, Anna. Sacred and Legendary Art – Volume 1. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longman’s & Roberts, 1987.

Please visit Christian Image Source for free Angel Clipart.

|

|

|

Archangel Michael

Archangel Michael

Archangel Art

Archangel Art Archangel Art

Archangel Art Archangel Michael

Archangel Michael

Archangel Pictures

Archangel Pictures

Apse Mosaic, San Vitale, Ravenna

Apse Mosaic, San Vitale, Ravenna

The Three Archangels from an Ancient Greek picture.

The Three Archangels from an Ancient Greek picture.

Guardian Angels

The Angel of Peace by Wilhem von Kaulbach

From the classification of the angelic hosts by the early theologians, and the special duties assigned to each class, we learn that the word angels, as ordinarily used, refers to archangels and angels only; these two classes are associated with human life in all its phases, while princedoms protect monarchies, thrones sustain the throne of God, cherubs continually worship, and seraphs adore the Most High. A belief in guardian angels those especially devoted to the care of individuals is far more widespread than the realism of the present day is inclined to admit. The godly man has a sure warrant for this trust in the ninety-first psalm:

We cannot think of angels as a reality in the winged, human forms that have been given them in Art, any more than we can look for mermaids to rise from the waters mentioned in the charming legends in which these maidens acted their parts. These imaginary and apparently palpable angels are but allegories, which long have been and continue to be the angels of Art, and we could not willingly give them up. We know that they are impossible, even fantastic, if we permit ourselves to be matter-of-fact; but as emblems of spiritual guardians, sent to mortals by an ever-watchful Father, we love them; and we wish to believe in guardian angels for those who are dear to us, even if we cannot realize them for ourselves.

In one of the early councils of the Church the form of angels was considered, and it was maintained by John of Thessalonica that they were in shape like men, and should be thus represented. This decision is supported by the supposition that God spoke to the angels when he said, “Let us make man after our image;” and again by Daniel, when he describes his heavenly visitors as “like unto the similitude of the sons of men.”

A guardian angel must be ever beside his charge from the beginning to the end of life, not only to guard from evil, but also to incite to good. In sorrow he is a comforter; in weakness, strength; even in death he is faithful, and contends against the evil spirits who fight for the possession of every soul; and after death he bears the spirit to St. Michael, the Lord of Souls. Thus is the guardian angel represented in Art, as is seen in above in the illustration called The Angel of Peace.

When we observe a beautiful, unselfish life that rises far above its surroundings, we recall the belief in angelic guardians, and the description which Milton gave of a chaste, saintly soul:

The impersonality of angels is one of their most precious qualities. An angel is never active except as the agent of the Almighty, deputed to manifest his mercy and love to the pious, or to inflict his punishments on the wicked. Thus angels must be perfect beings; and while they love to serve, their service is void of the personality which is inherent in all human service. When they sing together it is because some good has come to men, and when they mourn it is for human affliction.

According to the teaching of the Fathers of the Church to which we have referred, the combat between good and evil angels is unceasing, and they also warrant Christians in invoking the aid of angels, and believing them to be ever near to prevent evil and encourage good. From the views of the early theologians the artists evolved their manner of representing the hosts of heaven, and while for a time angels were represented as colossal, gradually they became more graceful and lovely, as well as more human.

An ideal, a thought, must be personified to be represented to the eye, and I doubt if any new personification of angels could satisfactorily replace that which has been developed in Art during sixteen centuries, and to which we are accustomed from our earliest childhood. The angels that are known in pictures, watching over children, preventing harm to individuals, as in the sacrifice of Isaac, encouraging or even compelling worthy action, as in the case of Balaam, are dear to the heart of the world.

Guardian Angel Pictures

Guardian Angel by Bartolome Esteban Murillo

The representations of guardian angels in the more homely relations, watching sleeping infants, guiding their feeble steps, as is seen in the image above, and shielding them from accidents, are modern. To the end of the sixteenth century guardian angels, while engaged in all these minor duties, according to the teaching of the Church, were only represented in Art as performing solemn and superhuman deeds.

This may have resulted from the fixed belief of the old artists in these angelic beings, and their deep reverence for them, while modern artists are simply seeking a graceful and poetic subject. But, be this as it may, the angels who perform miracles to prevent the torture of Christian martyrs and other superhuman acts, are as essentially guardian angels as are those bending over cradles and gathering blossoms for children in the fields.

Source: Clement, Clara Erskine. Angels in Art. Boston: L. C. Page and Company, 1898.