By Karen, on October 2nd, 2010

Archangels

The Seven

Who in God’s presence, nearest to His throne,

Stand ready at command. — Milton.

There are several angels who in artistic representations have assumed an individual form and character. These belong to the order of Archangels, placed by Dionysius in the third Hierarchy: they take rank between the Princedoms and the Angels and partake of the nature of both. Like the Princedoms, they have Powers; and, like the Angels, they are Ministers and Messengers.

Frequent allusion is made in Scripture to the seven Angels who stand in the presence of God. (Rev. viii. 2, xv. 1, xvi. 1, etc.; Tobit xxii. 15.) This was in accordance with the popular creed of the Jews, who not only acknowledged the supremacy of the Seven Spirits, but assigned to them distinct vocations and distinct appellations, each terminating with the syllable El, which signifies God. Thus we have —

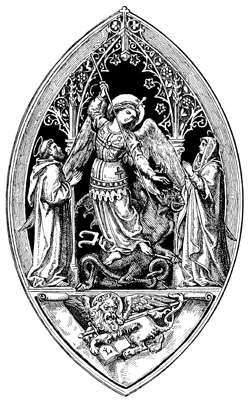

I. Michael (i. e. who is like unto God), captain-general of the host of heaven, and protector of the Hebrew nation.

II. Gabriel (i. e. God is my strength), guardian of the celestial treasury, and preceptor of the patriarch Joseph.

III. Raphael (i. e. the Medicine of God), the conductor of Tobit; thence the chief guardian angel.

IV. Uriel (i. e. the Light of God), who taught Esdras. He was also regent of the sun.

V. Chamuel (i. e. one who sees God), who wrestled with Jacob, and who appeared to Christ at Gethsemane. (However, according to other authorities, this was the angel Gabriel.)

VI. Jophiel (i. e. the Beauty of God), who was the preceptor of the sons of Noah, and is the protector of all those who, with a humble heart, seek after truth, and the enemy of those who pursue vain knowledge. Thus Jophiel was naturally considered as the guardian of the tree of knowledge, and the same who drove Adam and Eve from Paradise.

VII. Zadkiel (i. e. the Righteousness of God), who stayed the hand of Abraham when about to sacrifice his son. (But, according to other authorities, this was the archangel Michael.)

The Christian Church does not acknowledge these Seven Angels by name, neither in the East, where the worship of angels took deep root, nor yet in the West, where it has been tacitly accepted. Nor have they been met as a series, by name, in any ecclesiastical work of Art, though there is a set of old anonymous prints in which they appear with distinct names and attributes: Michael bears the sword and scales; Gabriel, the lily; Raphael, the pilgrim’s staff and gourd full of water, as a traveler. Uriel has a roll and a book: he is the interpreter of judgments and prophecies, and for this purpose was sent to Esdras.”The angel that was sent unto me, whose name was Uriel, gave me an answer.” (Esdras ii. 4.)

And in Milton —,

Uriel, for thou of those Seven Spirits that stand

In sight of God’s high throne, gloriously bright,

The first art wont his great authentic will

Interpreter through highest heaven to bring.

According to an early Christian tradition, it was this angel, and not Christ in person, who accompanied the two disciples to Emmaus. Chanmel is represented with a cup and a staff; Jophiel with a flaming sword. Zadkiel bears the sacrificial knife which he took from the hand of Abraham.

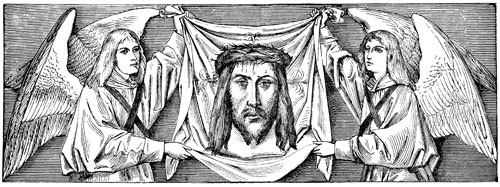

But the Seven Angels, without being distinguished by name, are occasionally introduced into works of art. For example, over the arch of the choir in San Michele, at Ravenna (A. D. 545), on each side of the throned Saviour are the Seven Angels blowing trumpets like cow’s horns: “And I saw the Seven Angels which stand before God, and to them were given seven trumpets.” (Rev. viii. 2, 6.) In representations of the Crucifixion and in the Pieta, the Seven Angels are often seen in attendance, bearing the instruments of the Passion. Michael bears the cross, for he is “the Bannerer of heaven,” but the particular avocations of the others is uncertain.

Archangels Archangels

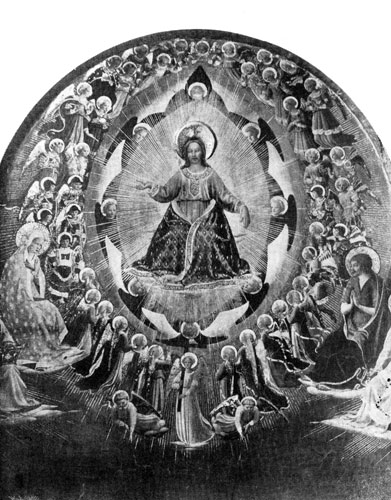

In the Last Judgment of Orcagna, in the Campo Santo at Pisa, the Seven Angels are active and important personages. The angel who stands in the center of the picture, below the throne of Christ, extends a scroll in each hand. On the scroll in the right hand is inscribed, “Come, ye blessed of my Father,” and on the scroll in the left hand, “Depart from me, ye accursed.” The angel is supposed to be Michael, the angel of judgment. At his feet crouches an angel, who seems to shrink from the tremendous spectacle, and hides his face. This angel is supposed to be Raphael, the guardian angel of humanity. The attitude has always been admired — cowering with horror, yet sublime. Beneath are another five angels, who are engaged in separating the just from the wicked, encouraging and sustaining the former, and driving the latter towards the demons who are ready to snatch them into flames. These Seven Angels have the garb of princes and warriors, with breastplates of gold, jeweled sword belts and tiaras, and rich mantles; while the other angels who figure in the same scene are plumed and bird-like, and hover above, bearing the instruments of the Passion.

Again we may see the Seven Angels in quite another character, attending on St. Thomas Aquinas, in a picture by Taddeo Gaddi. Here, instead of the instruments of the Passion, they bear the allegorical attributes of those virtues for which that famous saint and doctor is to be reverenced. One bears an olive-branch, i. e. Peace. The second holds a book, i. e. Knowledge. The third, a crown and sceptre, i. e. Power. The fourth holds a replica of a church, i. e. Religion. The fifth holds a cross and shield, i. e. Faith. The sixth holds flames of fire in each hand, i.e. Piety and Charity. Finally, the seventh angel holds a lily, i. e. Purity.

In general it may be presumed that when seven angels figure together, or are distinguished from among a host of angels by dress, stature, or other attributes, that these represent “the Seven Holy Angels who stand in the presence of God.” Four only of these Seven Angels are individualized by name: Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, and Uriel. According to the Jewish tradition, these four sustain the throne of the Almighty; they have the Greek epithet arch, or chief, assigned to them, from the two texts of Scripture in which that title is used (1 Thess. iv. 16 ; Jude 9), but only the three first, who in Scripture have a distinct personality, are reverenced in the Catholic Church as saints, and their gracious beauty, divine prowess, and high behests to mortal man have furnished some of the most important and most poetical subjects which appear in Christian Art.

Source: Jameson, Anna. Sacred and Legendary Art – Volume 1. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longman’s & Roberts, 1987.

Be sure to visit Christian Image Source for free images of Archangels.

By Karen, on September 18th, 2010

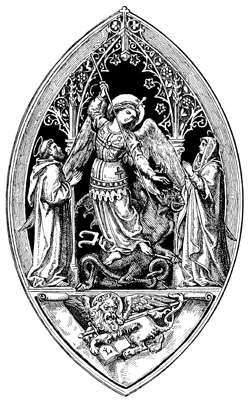

Michael the Archangel Michael the Archangel

The Supernatural in the Angelic World

Supernatural Vocation of the Angels

I. Holy Scripture hints that all the angels were called to the vision of God, when it represents the good angels as actually seeing His Face, and only excludes the fallen ones of from that privilege. Such is also the common tradition embodied in the opinion that man was called to fill the places left vacant by the fallen angels. At any rate, the supernatural vocation of man affords the strongest presumption for a similar vocation of the angels. The fact that many of them did fall supposes that they had to go through a trial, and to merit salvation. Like man, they were unable to attain supernatural life without the aid of actual and habitual grace.

Grace Granted to the Angels

(1.) It is morally certain that all the angels once possessed sanctifying grace. Holy Scripture alludes to this fact, while patristic tradition is unanimous about it. The Fathers generally apply to the angels the texts Ezech. xxviii. and Isai. xiv. 12, which, however, taken literally, only refer to the kings of Tyre and Babylon. A better, though by no means a cogent proof is afforded by John viii. 44, combined with Jude i. 6: “The devil stood not in the truth” “the angels who kept not their principality.” Truth, in the language of the New Testament, means truth founded on grace and justice; and principality implies a dignity so high that we can hardly conceive it to have been unadorned with grace.

The tradition of the Fathers is unanimous that the angels also received grace in the moment of their creation. Theologians generally admit that the diversity of rank among the angels is an indication of diversity of grace received, because, on account of his unimpaired free will, every angel attained at once all the perfection possible to him. It may further be supposed that God created the angels with an amount of natural perfection proportionate to the measure of grace predestined to each of them, and also that the measure of grace given to the angels surpasses that given to men. Yet it is quite possible that some human beings attain to a higher degree of perfection than angels. That the Queen of Angels did so is taught expressly by the Church.

Grace was necessarily accompanied by the virtue of Faith and the knowledge of the supernatural order, culminating in the clear vision of God; because, without these. supernatural life in the state of probation is impossible. Most probably the knowledge of the supernatural order included a knowledge of the Trinity, and of the future Incarnation of the Logos, as these dogmas are so intimately connected with the order of grace.

Merit of the Angels

(2.) The meritorious acts performed by the angels in consequence of the grace received, consisted in the free fulfilling of the supernatural law of God, or in the full subjection to God as the Author of grace and glory. The angels who persevered must have performed at least this one act of submission. But as regards the circumstances of this act, we have only more or less probable opinions. E.g., it may be that a special law of probation, analogous to that given to Adam, was given to the angels, and that it consisted in a restriction of their natural exaltedness above human nature, just as the commandment given to man consisted in a restriction of his dominion over visible nature.

Angels and Beatific Vision

(3.) From the words of Christ, “Their angels in heaven always see the Face of My Father Who is in heaven” (Matt. xviii. 10), we learn that, unlike the Patriarchs, the angels were admitted to the immediate vision of God as soon as they merited it. There is no reason why there should have been any interval.

Relations of the Angels to Mankind

II. The angels hold the first rank in the order of grace as well as in the order of nature. They actually possess the supernatural perfection to which man is but tending, and are therefore his model in the service and praise of God.

(1.) As the first-born of creation, they are called to cooperate in the Divine government of the world, and especially in carrying out the supernatural order in mankind. The nature of their cooperation results from the fellowship of all rational creatures, by reason of which they are one city of the saints, one temple of God, offering to God by Charity one great sacrifice. Men are fellow-citizens of the angels, or, rather, members of the same family of which God is the Father, and in which the perfect members are the born protectors and helpers of the yet imperfect members. St . Paul expresses this idea when he calls the heavenly Jerusalem “our mother” (Gal. iv. 26). Man requires the protection of the good angels, not only because of his natural weakness, but also in order to resist the onslaught of the fallen angels, the princes and powers of darkness.

Guardian Angels Guardian Angels

Guardian Angels

(2.) It is an article of faith that the angels are “ministering spirits, sent to minister for those who shall receive the inheritance of salvation” (Heb. i. 14). As Divine ambassadors and messengers they minister to man, not indeed as servants of man, but as servants of God. Theymact as guardians, guides, pedagogues, tutors, pastors, set over their weaker brethren by the common Father: “ He hath given His angels charge over thee, to keep thee in all thy ways” (Ps. xc. 11). At times they also execute the decrees of Divine justice, e.g. Gen. iii. 24; Exod. xxii., 27.; 1 Paral. xxi. 16.

From many indications in Holy Writ, and from constant tradition, the guardianship of man is divided among the angels according to a fixed order, so that different spheres of action are assigned to different angels. Thus different nations and greater corporations, especially the several parts of the Church of God, are committed to the permanent charge of particular angels. The guardian angels of the Jews, Persians, and Greeks are mentioned Dan. x. 13, 20, 21, and xii. I: “ Now I will return to fight against the prince of the Persians. When I went forth, there appeared the prince of the Greeks coming, and none is my helper in all these things but Michael your prince” (Dan. x. 20, 21). The title of prince given to the guardian angel implies a permanent office among the same people. The proof that the care of individual men is entrusted to angels is found in Matt, xviii. 10: “Take heed that you despise not one of these little ones; for I say to you that their angels in heaven always see the face of My Father Who is in heaven.” The first Christians testified to this doctrine when they thought it was not St. Peter but “his angel” who stood in their presence (Acts xii. 6 ; Psalm xxxiii. 8, and Heb. i. 14). The doctrine that “every one of the faithful is guarded by one or more angels,” although not exactly a matter of faith, is yet theologically certain, and to deny it would be rash. It is simply a consequence of the fellowship which Baptism establishes between man and angels. It is less certain, but still highly probable, that even the unbaptized are under the special custody of angels, on account of their supernatural vocation.

The common belief that each individual has his own guardian angel, or that there are as many guardian angels as men, is not so certain as the more general doctrine that all men are guarded by angels. It is quite possible for one angel to guard and protect several individuals

Office of the Guardian Angels

(a). The functions of the guardian angels have chiefly to do with the eternal salvation of their charges, but, like Divine Providence and neighbourly love, they extend also to assistance in matters temporal. In matters spiritual the guardian angels behave towards us as tender and conscientious parents towards their children. They protect us against our invisible enemies, either by preventing the attack or by helping us to resist. They pray for us, and offer our prayers and good works to God.

Lastly, they conduct the souls to the judgment seat of God, and introduce them into eternal glory (Luke xvi. 22). The communication of the dead with the living, e.g. apparitions and death-warnings, are probably the work of guardian angels, as may also be the bilocation related of several saints.

Worship Due to the Guardian Angels

(b). The position of the angels with regard to man entitles them to a worship consisting of love, respect, and reverence. Our fellowship with the family of God requires mutual love between the members; the excellent dignity of the angels demands grateful and submissive homage, but neither adoration nor slavish submission (Apoc. xxii 8, 9).

Source: Wilhelm, Joseph and Thomas B. Scannell. A Manual of Catholic Theology: Based on Scheeben’s “Dogmatik”, Volume 1. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Lt., 1906.

Visit Christian Image Source for free Guardian Angel Pictures.

By Karen, on September 18th, 2010

Cherub Pictures Cherub Pictures

Number and Hierarchy of the Angels

Number of the Angels

I. We are certain, from Revelation. that the number of Angels is exceedingly great, forming an army worthy ot the greatness of God. This army of the King of heaven is mention in Deut. xxx. 2; then in the vision of Daniel (vii. 10), and in many other places.

How Many Kinds?

II. If the Angels can be numbered, there must exist between them at least personal differences; that is to say, each angel has his own personality. But whether they are all of the same kind, like man, or constitute several kinds, or are each of a different kind or species, is a question upon which Theologians differ.

The Nine Choirs

III. The Fathers have divided the Angels into nine Orders or Choirs, the names of which are taken from Scripture. They are: Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones, Dominations, Virtues, Powers, Principalities, Archangels and Angels. The first two and the last two orders are often named in Holy Writ; the five others are taken from Ephes. i. 21 and Col. i. 16. It seems clear enough, especially if we take into account the all but unanimous testimony of the Fathers, that these names designate various Orders of Angels; whence it follows that there are at least nine such Orders—not, however, that there are only nine. Considering, however, that for the last thirteen centuries the number nine has been accepted as the exact number of angelical Choirs, we are justified in accepting it as correct.

It is impossible to determine the differences between the several Orders of Angels with anything like precision. The three highest Orders bear names which seem to point to constant relations with God, as if these Angels formed especially the heavenly court; the three lowest express relations to man; the three middle ones only point to might and power generally.

The fallen angels probably retain the same distinctions as the good ones, because these distinctions are, in all likelihood, founded upon differences in natural perfections. Scripture speaks of “the prince of demons” (Matt. xii. 24), and applies some of the names of angelic Orders to bad angels (Eph. vi. 12).

Source: Wilhelm, Joseph and Thomas B. Scannell. A Manual of Catholic Theology: Based on Scheeben’s “Dogmatik”, Volume 1. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Lt., 1906.

Visit Christian Image Source for free images of Seraphim Angels.

By Karen, on September 18th, 2010

Drawings of Angels Drawings of Angels

Attributes of the Angels—Incorruptibility and

Relation to Space

The attributes of the Angels, like the nature of their substance, are to be determined by a comparison with the attributes of God on the one hand, and with the attributes of man on the other. As creatures, the Angels partake of the imperfections of man; as pure spirits, they partake of the perfections of God.

Incorruptibility

I. The angelic substance is physically simple—that is, not composed of different parts; but it is not metaphysically simple, because it admits of potentiality and actuality, and also of accidents (§ 63). It is, moreover, essentially immutable or incorruptible; Angels cannot perish by dissolution of their substance, nor can any created cause destroy them. For this reason they are essentially immortal, not, indeed, that their destruction is in itself an impossibility, but because their substance and nature are such that, when once created, perpetual conservation is to them natural. As to accidental perfections, Angels can acquire and lose them. Observe, however, that the knowledge they once possess always remains, and that a loss of perfection can only consist in a deviation from goodness.

Angels differ from the human soul in this, that they neither are nor can be substantial forms informing a body. When they assume a body, their union with it is neither like that of soul and body, nor like the hypostatic union of the two natures in Christ. The assumed body is, as it were, only an outer garment, or an instrument for a transitory purpose.

Relation to Space

II. As regards relation to space, Angels, having like God no extended parts, cannot occupy a place so that the different portions of space correspond with different portions of their substance, nor do they require a corporal space to live in, nor can any such space enclose them. On the other hand, they differ from God in this, that they can be present in only one place at a time, and thus can move from place to place. Their motion is, however, unlike that of man; probably it is as swift as thought, or even instantaneous.

The Natural Life and Work of the Angels

Life of the Angels

I. The life of the Angels is purely intellectual, without any animal or vegetative functions, and therefore more like the Divine Life than the life of the human soul. The whole substance of an Angel is alive, whereas, in man, one part is life-giving and another life-receiving. The angelic life is inferior to the Divine in this, that the Angel’s life is not identical with its substance; and also in this, that it is susceptible of increase and decrease in perfection. So far all Theologians agree. But they differ very considerably as to how Angels live—that is, how and what they think and will. Leaving aside the abstruse speculations on this subject, we shall here only touch on the few points in which anything like certitude is attainable.

Intellect and Knowledge of the Angels

II. It is certain from Revelation that the natural intellect of Angels is essentially more perfect than the human, and essentially less perfect than the Divine Intellect. Thus Scripture makes the knowledge of Angels the measure of human knowledge, e.g. 2 Kings xiv. 20; and in Mark xiii. 32, Christ says that even the Angels—much less man—do not know the time of the last judgment. The Fathers call the angels intelligentias,—that is, beings possessed of immediate intuitive knowledge; but man they call rationalis—that is, a being whose knowledge is for the most part inferential: whence the superiority of angelic knowledge is manifest. Compared to the Divine Knowledge, the imperfection of the angelic, according to Scripture and the Fathers, consists in this, that the Angels cannot naturally see God as He is, by immediate, direct vision; that they cannot penetrate the secrets either of the Divine decrees, or of the hearts of man, or of each other; much less do they know future free actions.

The Will of Angels

III. As to the will of the Angels, we can only gather from Revelation that it naturally possesses the perfection of the human will, but at the same time also shares to some extent in the imperfections of the latter. The angelic will is free as to the choice of its acts, and is able to perform moral actions and to enjoy true happiness. But it is not, by virtue of its nature, directed to what is morally good; its choice may fall on evil. This much can be gathered from what is revealed on the fall of the Angels.

External Power and Activity of the Angels

IV. It is evident that the Angels are able to perform all the actions of man, except those which are peculiar to man on account of his composite nature. Revelation, moreover, introduces Angels acting in various ways: they speak, exhort, enlighten, protect, move, and so forth. It is also beyond doubt that the power of Angels is superior to that of man, both as regards influence on material things, and on man himself. As to the mode of action, we know, but little with certainty. The Angel acts by means of his will, like God; but he neither creates out of nothing, nor generates like man. The only immediate effect an Angel can produce by an act of his will, is to move bodies or forces so as to bring them into contact or separate them, and thus to influence their action. Bodies are moved from place to place locally; spirits or minds are only moved “intentionally;” that is, the Angel who wishes to act upon our souls or upon other spirits, puts an object before them and directs their attention towards it. The power of Angels over matter exceeds that of man as regards the greater masses they are able to move and the velocity and exactness or appropriateness of the motion. These advantages enable them to produce effects supernatural in appearance, although entirely owing to a higher knowledge of the laws of nature and to superior force. As this power belongs to the angelic nature it is common to both good and bad Angels.

Angelic speech would seem to consist simply in this, that the speaker allows the listener to read so much of his thoughts as he wishes to communicate. Hence Angels can converse at any distance; the listener sees the thought of the speaker, and thus all possibility of error or deception is excluded.

Power of the Angels over Man

V. Angels have over the body of man the same power as over other material bodies. Over the human mind, however, their power is circumscribed within narrow limits. They cannot speak to man as they speak to each other, because the mind of man is unable to grasp things purely spiritual. But, by their power over matter, they can exercise a great influence on the lower life of the soul, and thus indirectly on its intellectual life also. They can propose various objects to the senses, and also move the sense-organs internally; they can act on the imagination, and feed it with various fancies; and lastly, as the intellect takes its ideas from the imagination, Angels are enabled to guide and direct the noblest faculty of man either for better or for worse.

Source: Wilhelm, Joseph and Thomas B. Scannell. A Manual of Catholic Theology: Based on Scheeben’s “Dogmatik”, Volume 1. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Lt., 1906.

Visit Christian Image Source for free Angel Images.

By Karen, on September 18th, 2010

Angel Drawings Angel Drawings

The Nature, Existence, and Origin of the Angels

Terminology

I. The name “ Angel”—that is, messenger or envoy—designates an office rather than a nature, and this office is not peculiar to the beings usually called Angels. Holy Scripture, however, and the Church have appropriated this name to them, because it represents them as standing between God and the rest of the universe, above man and nearer to God on account of their spiritual nature, and taking a share in the government of this world, although absolutely dependent on God. In this way the term “Angel” is even more expressive of their nature than the terms “spirit,” or “pure spirit,” because these latter, if not further determined, are applicable also to God. In order to prevent the belief that all superhuman beings are gods, the documents of Revelation, when speaking of these higher beings, always style them Angels, or Zebaoth—that is, the army of God. Evil spirits, being sufficiently distinguished from God by their wickedness, are often called “spirits,” “bad and wicked spirits,” and sometimes also “angels.” The Greek name daemon (“the knowing or knowledge-giving”) is applied, in Holy Writ, exclusively to the spirits of wickedness, because they resemble God only in knowledge, and only offer knowledge to men in order to seduce them.

The Nature of Angels

II. We conceive the Angels as spiritual beings of a higher kind than man, and more like to God; not belonging to this visible world, but composing an invisible world, ethereal and heavenly, from which they exercise, with and under God, a certain influence on our world.

The Existence of Angels

III. The existence of Angels is an article of Faith, set forth alike in innumerable passages of Holy Scripture and in the Symbols of the Church. Scripture does not expressly mention the Angels in its narrative of Creation, but St. Paul (Col. i. 16) enumerates them among the things created through the Logos, and divides these “invisible beings” into Thrones, Dominations, Principalities and Powers. From Genesis to the Apocalypse the sacred pages everywhere bear witness to the existence and activity of the Angels. It is most probable that their existence was part of the primitive revelation, the distorted remains of which are found in polytheism. Unaided reason can neither prove nor disprove the existence of pure spirits, but it can show the fittingness of their existence.

Angels are Creatures

IV. It is likewise an article of Faith that the Angels were created by God. They are not emanations from His Substance, or the result of any act of generation or formation, but were made out of nothing. All other modes of origin are inconsistent with the spiritual nature of God and of the Angels themselves. Nor can they be eternal or without origin, because this is the privilege of the Infinite. However, inasmuch as the real reason why Angels are not procreated by generation is their immateriality, and inasmuch as this immateriality is an article of Faith, it follows that we are bound to believe that no Angel has been generated.

Angels had a Beginning

V. The Fourth Lateran and the Vatican Councils have defined that Angels were not created from all eternity, but that they had a beginning. “God . . . at the very beginning of time made out of nothing both kinds of creatures, spiritual and corporal, angelic and mundane” (sess. iii., c. 1). That the creation of the Angels was contemporaneous with the creation of the world, is not defined so clearly, and, therefore, is not a matter of Faith. The words “simul ab initio temporis,” according to St. Thomas (Opusc. xxiii.), admit of another interpretation, and the definition of the Lateran Council was directed against errors not bearing directly on the time of the creation of the Angels. The probabilities, however, point in the direction of a simultaneous creation: the universe being the realization of one vast plan for the glory of God, it might be expected that all its parts were created together.

Where were the Angels Created?

VI. It is not easy to decide where the Angels were created. Although their spiritual substance requires no bodily (corporeal) room, still, considering that they are part and parcel of the universe, it is probable that they were created within the limits of the space in which the material world is contained. As they are not bound or tied to any place, it is vain to imagine where they dwell. When Scripture makes heaven their abode, this only implies that they are not tied to the earth, like man, but that the whole of the universe is open to them.

Source: Wilhelm, Joseph and Thomas B. Scannell. A Manual of Catholic Theology: Based on Scheeben’s “Dogmatik”, Volume 1. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Lt., 1906.

Visit Christian Image Source for Free Angel Pictures.

By Karen, on September 13th, 2010

Religious Angels Religious Angels

[Part 1]

(6) In Human Form

In the Scriptures angels appear with bodies, and in the human form, and no intimation is anywhere given that these bodies are not real, or that they are only assumed for the time and then laid aside. It was manifest indeed to the ancients that the matter of these bodies was not like that of their own, inasmuch as angels could make themselves visible and vanish again from their sight. But this experience would suggest no doubt of the reality of their bodies; it would only intimate that they were not composed of gross matter. After his resurrection Jesus often appeared to his disciples and vanished again before them; yet they never doubted that they saw the same body which had been crucified, although they must have perceived that it had undergone an important change. The fact that angels always appeared in the human form does not, indeed, prove that they really have this form, but that the ancient Jews believed so. That which is not pure spirit must have some form or other, and angels may have the human form, but other forms are possible. We sometimes find angels, in their terrene manifestations, eating and drinking (Gen. xviii:8; xix:3), but in Judg. xiii:15, 16, the angel who appeared to Manoah declined, in a very pointed manner, to accept his hospitality. The manner in which the Jews obviated the apparent discrepancy, and the sense in which they understood such passages, appears from the apocryphal book of Tobit (xii:19), where the angel is made to say, ‘It seems to you, indeed, as though I did eat and drink with you, but I use invisible food, which no man can see.’ Milton, who was deeply read in the ‘angelical’ literature, derides these questions:

So down they sat

And to their viands fell; nor seemingly

The angel, nor in mist (the common gloss

Of theologians), but with keen dispatch

Of real hunger, and concoctive heat

To transubstantiate; what redounds

Transpires through spirits with ease.

–Paradise Lost, v:433-439.

The same angel had previously satisfied the curiosity of Adam on the subject, by stating that

Whatever was created, needs

To be sustained and fed.

If this dictum were capable of proof, except from the analogy of known natures, it would settle the question. But if angels do not need it, if their spiritual bodies are inherently incapable of waste or death, it seems not likely that they gratuitously perform an act designed, in all its known relations, to promote growth, to repair waste and to sustain existence.

The passage already referred to in Matt. xxii:30, teaches by implication that there is no distinction of sex among the angels. The Scripture never makes mention of female angels. The Gentiles had their male and female divinities, who were the parents of other gods. But in the Scriptures the angels are all males, and they appear to be so represented not to mark any distinction of sex, but because the masculine is the more honorable gender. Angels are never described with marks of age, but sometimes with those of youth (Mark xvi:5). The constant absence of the features of age indicates the continual vigor and freshness of immortality. The angels never die (Luke xx:36). But no being besides God himself has essential immortality (I Tim. vi:16) ; every other being therefore is mortal in itself and can be immortal only by the will of God. Angels, consequently, are not eternal, but had a beginning.

Free Angel Pictures

(7) Attributes

The preceding considerations apply chiefly to the existence and nature of angels. Some of their attributes may be collected from other passages of Scripture. That they are of superhuman intelligence is implied in Mark xiii:32: ‘But of that day and hour knoweth no man, not even the angels in heaven.’ That their power is great may be gathered from such expressions as ‘mighty angels’ (2 Thess. i:7) ; ‘angels powerful in strength’ (Ps. cii:20); ‘angels who are greater (than man) in power and might.’ The moral perfection of angels is shown by such phrases as ‘holy angels’ (Luke ix:26); ‘the elect angels’ (2 Tim. V:21). Their felicity is beyond question in itself, but is evinced by the passage (Luke xx:36) in which the blessed in the future world are said to be ‘like unto the angels and sons of God.’

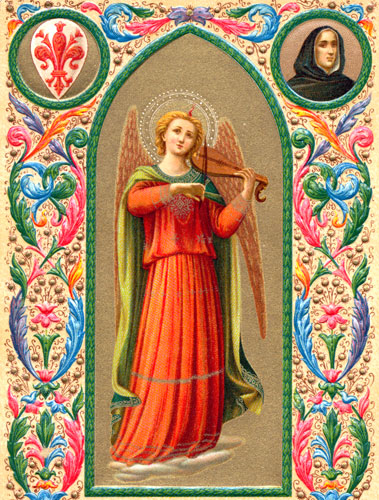

Archangel Gabriel Archangel Gabriel

(8) Ministry

The ministry of angels, or that they are employed by God as the instruments of His will, is very clearly taught in the Scriptures. The very name, as already explained, shows that God employs their agency in the dispensations of His Providence. And it is further evident, from certain actions which are ascribed wholly to them (Matt. xiii:41, 49; xxiv:31; Luke xvi:22), and from the Scriptural narratives of other events, in the accomplishment of which they acted a visible part (Luke i:11, 26; ii:9, sq.; Acts v:19, 20; x:3, 19; xii:7; xxvii:23), that their agency is employed principally in the guidance of the destinies of man. In those cases also in which the agency is concealed from our view, we may admit the probability of its existence, because we are told that God sends them forth ‘to minister to those who shall be heirs of salvation’ (Heb. i:14; also Ps. xxxiv:8, 91 ; Matt. xviii:10). But the angels, when employed for our welfare, do not act independently, but as the instruments of God, and by His command (Ps. ciii:20; civ: 4: Heb. i:13, 14) ; not unto them, therefore, are our confidence and adoration due, but only unto Him (Rev. xix:10; xxii:9) whom the angels themselves reverently worship.

Guardian Angel Pictures Guardian Angel Pictures

(9) Guardianship

It was a favorite opinion of the fathers that every individual is under the care of a particular angel, who is assigned to him as a guardian. The Jews (excepting the Sadducees) entertained this belief, as do the Moslems. The heathen held it in a modified form—the Greeks having their tutelary daemon and the Romans their genius. There is, however, nothing to support this notion in the Bible. The passages (Ps. xxxiv:7; Matt. xviii:10) usually referred to in support of it have assuredly no such meaning. The former, divested of its poetical shape, simply denotes that God employs the ministry of angels to deliver his people from affliction and danger, and the celebrated passage in Matthew cannot well mean anything more than that the infant children of believers, or, if preferable, the least among the disciples of Christ, whom the ministers of the church might be disposed to neglect from their apparent insignificance, are in such estimation elsewhere that the angels do not think it below their dignity to minister to them.

(Literature: Storr & Flatt’s Lehrbuch der Ch. Dogmatik, Sec. xlviii; Dr. L. Mayer, Scriptural Idea of Angels, in Am. Bib. Repository, xii :356-388; Moses Stuart’s Sketches of Angelology in Robinson’s Bibliotheca Sacra, No. I; Merheim, Hist. Angelor. Spec.; Schulthens, Engelwelt; etc.)

Source: From Fallows, Samuel, Ed. The Popular and Critical Bible Encyclopaedia and Scriptural Dictionary, Volume 1. Chicago: The Howard-Severance Company, 1914.

Visit Christian Image Source to get free images of Heavenly Angels.

By Karen, on September 12th, 2010

Angel Graphics Angel Graphics

Angel, is a word signifying messengers, both in Hebrew and Greek, and therefore used to denote whatever God employs to execute his purposes, or to manifest his presence or his power. In some passages it occurs in the sense of an ordinary messenger (Job i:14; I Sam. xi:3; Luke Vii:4; iX:52); in others it is applied to prophets (Is. lxiii:i9; Bag. i:13; Mal. iii); to priests (Eccl. v:5: Mal. ii:7); to ministers of the New Testament (Rev. i:20). It is also applied to personal agents; as to the pillar of cloud (Exod. xiv:19; xiii:21;xxxii:34); to the pestilence (2 Sam. xxiv:16, 17;2 Kings xix:30); to the winds (‘who maketh the winds his angels’ Ps. civ:4); so, likewise, plagues generally are called ‘evil angels’ (Ps. lxxviii:49), and Paul calls his thorn in the flesh an ‘angel of Satan’ (2 Cor. xii:7; Gal. iv:13, 14).

Angel Pictures Angel Pictures

(1) Spiritual Beings

But this name is more eminently and distinctively applied to certain spiritual beings or heavenly intelligences, employed by God as the ministers of His will and usually distinguished as angels of God or angels of Jehovah. In this case the name has respect to their official capacity as “messengers,” and not to their nature or condition. The term ‘spirit,’ on the other hand (in Greek, pneuma, in Hebrew mach), has reference to the nature of angels, and characterizes them as incorporeal and invisible essences. But neither the Hebrew mach nor the Greek pneuma, nor even the Latin spiritus, corresponds exactly to the English spirit, which is opposed to matter, and designates what is immaterial; whereas the other terms are not opposed to matter, but to body, and signify not what is immaterial, but what is incorporeal. The modern idea of spirit was unknown to the ancients. They conceived spirits to be incorporeal and invisible, but not immaterial, and supposed their essence to be a pure air or a subtile fire. The proper meaning of pneuma (from I blow, I breathe) is air in motion, wind, breath.

Angel Images

(2) Spiritual Bodies

The Hebrew mach is of the same import; as is also the Latin spiritus, from spiro, I blow, I breathe. When, therefore, the ancient Jews called angels spirits, they did not mean to deny that they were endued with bodies. When they affirmed that angels were incorporeal, they used the term in the sense in which it was understood by the ancients—that is, as free from the impurities of gross matter. The distinction between ‘a natural body’ and ‘a spiritual body’ is indicated by St. Paul (I Cor. xv:44), and we may, with sufficient safety, assume that angels are spiritual bodies, rather than pure spirits in the modern acceptation of the word.

It is disputed whether the term Elohim is ever applied to angels, but the inquiry belongs to another place. It may suffice here, perhaps, to observe that both in Ps. viii:5 and xcvii:7 the word is rendered by angels in the Sept. and earlier ancient versions; and both these texts are 1) cited in Heb. i:6; ii:7, that they are called Beni-Elohim, Sons of God.

Christian Angels Christian Angels

(3) Spiritual Intelligences

In the Scriptures we have frequent notices of spiritual intelligence, existing in another state of being, and constituting a celestial family, or hierarchy, over which Jehovah presides. The Bible does not, however, treat of this matter professedly and as a doctrine of religion, but merely adverts to it incidentally as a fact, without furnishing any details to gratify curiosity. It speaks of no obligations to these spirits, and indicates no duties to be performed towards them. A belief in the existence of such beings is not, therefore, an essential article of religion, any more than a belief that there are other worlds besides our own; but such a belief serves to enlarge our ideas of the works of God, and to illustrate the greatness of his power and wisdom (Mayer, Am. Bib. Repos. xii:360). The practice of the Jews, of referring to the agency of angels every manifestation of the greatness and power of God, has led some to contend that angels have no real existence, but are mere personifications of unknown powers of nature; and we are reminded that, in like manner, among the Gentiles, whatever was wonderful, or strange, or unaccountable, was referred by them to the agency of some one of their gods. Among the numerous passages in which angels are mentioned, there are, however, a few which cannot, without improper force, be reconciled with this hypothesis (Gen. xvi:7-12; Judg. xiii:1-21; Matt. xxviii:2-4), and if Matt. xx:30 stood alone in its testimony, it ought to settle the question. Christ there says that ‘in the resurrection they neither marry nor are given in marriage, but are as the angels of God.’ The force of this passage cannot be eluded by the hypothesis that Christ mingled with his instructions the erroneous notions of those to whom they were addressed, seeing that he spoke to Sadducees, who did not believe in the existence of angels (Acts xxiii:8). So likewise, the passage in which the high dignity of Christ is established, by arguing that he is superior to the angels (Heb. i:4, sqq.), would be without force or meaning if angels had no real existence.

Pictures of Angels Pictures of Angels

(4) Numerous

That these superior beings are very numerous is evident from the following expressions: Dan. vii:10, ‘thousands of thousands,’ and ‘ten thousand times ten thousand.’ Ps. lxviii:17; Matt. xxvi:53, ‘more than twelve legions of angels.’ (Comp. Gen. xxviii:12; xxxii: 1, 2; Ps. ciii:20, 21 ; cxlviii:2). Luke ii:13, ‘multitude of the heavenly host.’ Heb. xii:22 23, ‘myriads of angels.’ It is probable, from the nature of the case, that among so great a multitude there may be different grades and classes, and even natures—ascending from man towards God, and forming a chain of being to fill up the vast space between the Creator and man—the lowest of his intellectual creatures. This may be inferred from the analogies which pervade the chain of being on the earth whereon we live, which is as much the Divine creation as the world of spirits.

Archangel Michael Archangel Michael

(5) Biblical Allusions

Accordingly the Scripture describes angels as existing in a society composed of members of unequal dignity, power and excellence, and as having chiefs and rulers, It is admitted that this idea is not clearly expressed in the books composed before the Babylonish captivity; but it is developed in the books written during the exile and afterwards, especially in the writings of Daniel and Zechariah. In Zech. i:11 an angel of the highest order, one who stands before God, appears in contrast with angels of an inferior class, whom he employs as his messengers and agents (Comp. iii:7). In Dan. x:13, the appellation, “one of the chief princes,” and in xii:I, “the great prince,” are given to Michael. The Grecian Jews rendered this appellation by the term archangel, which occurs in the New Testament (Jude 9;1 Thess. iv:16),where we are taught that Christ wilt appear to judge the world with the voice of an archangel. This word denotes, as the very analogy of the language teaches, a chief of the angels, one superior to the other angels, like the term chief priest. The opinion, therefore, that there were various orders of angels was not peculiar to the Jews, but was held by Christians in the time of the apostles, and is mentioned by the apostles themselves. The distinct divisions of the angels, according to their rank in the heavenly hierarchy, which we find in the writings of the later Jews, were either almost or wholly unknown in the apostolical period.

Source: Fallows, Samuel, Ed. The Popular and Critical Bible Encyclopaedia and Scriptural Dictionary, Volume 1. Chicago: The Howard-Severance Company, 1914.

Please visit Christian Image Source for free Drawings of Angels.

By Karen, on September 11th, 2010

Triumph of the Innocents by Holman Hunt

[Part 1] [Part 2] [Part 3] In this front rank of great religious artists we must also place Mr. Holman Hunt, whose work has appealed so strongly to the popular mind, without any deliberate attempt on his part, however, to make it do so. His great picture, “The Triumph of the Innocents,” demands mention here for the beauty of the angelic children who, seen alone by the infant Christ, are accompanying the Holy Family to Egypt. The picture was at the Guildhall Exhibition a year or two ago, and is now in the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

Elijah in the Wilderness by Lord Frederick Leighton

The religious works of the late Lord Leighton are few, and the “Elijah,” reproduced on page 771, is probably the best. The angel is a striking figure, enriched as it is by the beauty of eternal youth; but it will he noticed that the artist’s love for carefully arranged draperies is exemplified even here. This picture is also at Liverpool. It is not generally known that Lord Leighton many years ago was engaged with other great artists living in “the ‘Sixties” in the illustration of an edition of the Bible. No book has suffered more through its illustrations than the “Book of books,” and this effort to do it justice is worthy of note here. Many of the drawings executed are to be seen in South Kensington Museum.

Elijah Is Nourished by an Angel by Gustave Dore

It is doubtful if any illustrated Bible exceeded the popularity attained by the one illustrated throughout by Gustave Dore. This talented Frenchman had a versatility of genius truly remarkable, and during his comparatively short life accomplished more work than any artist of any time. With an imagination which could grasp any incident pictorially, he was equally happy in illustrating the Bible, Milton’s or Dante’s works, “Don Quixote” or “Aesop’s Fables.” His angels, while being conventional and in full accord with popular ideas, were

spiritual and ethereal, as the example given on page 774 is sufficient to show.

He was peculiarly happy in delineating the heavenly hosts, and seemed to revel

in illustrating such a passage from

Dante as the following:—

“In fashion, as a snow white rose, lay then

Before my view the saintly multitude.

Which in His own blood Christ espoused. Meanwhile

That other host, that soar aloft to gaze

And elaborate His glory, whom they love,

Hovered around: and like a troop of bees,

Amid the vernal sweets alighting now,

Now clustering where their fragrant labour glows,

Flew downward to the mighty flower, or rose

From the redundant petals, streaming back

Unto the steadfast dwelling of their joy.

Faces had they of flame, and wings of gold;

The rest was whiter than the driven snow;

And, as they flitted down the flower,

From range to range, fanning their plumy loins,

Whispered the peace and ardour, which they won

From that soft winnowing.”

“Paradise,” Canto xxxi

In Milton’s “Paradise Lost,” too, Dore found delight in depicting the scenes in heaven as described by the inspired poet. The following passage afforded him one of his finest opportunities:—

“Then crowned again, their golden harps they took.

Harps ever tuned, that glittering by their side

Like quivers hung, and with preamble sweet

Of charming symphony they introduce

Their sacred song, and waken raptures high:

No voice exempt, no voice but well could join

Melodious part, such concord is in heaven.”

Angels Adoring the Infant Christ by Marianne Stokes

The illustration on p. 775 is from a picture by one of our most eminent lady artists, Mrs. Adrian Stokes. She has painted several religious pictures, each alike endowed with beauty and the true spirit of simplicity and reverence. In the picture before us she has departed from the conventional idea of the angel quite as much as Rossetti or Sir Edward Burne-Jones has done; but in another work I remember of hers—“Angels Adoring the Infant Christ”—she has given us delightful transcripts from the early Italian masters in the figures of the angels.

Angel Clipart Angel Clipart

The pictorial representations of angels reproduced in this paper are given as types of the various creations of painters. Each succeeding exhibition of works of art contains some fresh attempt to portray the angelic beings; but it will be found that each one is based upon one or other of the ideas represented in these articles. The artist may, of course, have his own method of painting and infuse individuality into his work, but the characteristic features of the angel remain. Compare these illustrations of modern work with those given or mentioned in the opening paper on the subject, and it will be found that the most unconventional of them has its counterpart in, or a least points of resemblance to, the creations of the early artists. We come back, then, to the point raised in that article, that we are indebted entirely to the early artists of Italy for the idea of the angelic form. I pointed out that in the Bible no description is afforded us of angels, and the fact has to be recognised that the popularly accepted form of the heavenly messenger is entirely a creation of the mediaeval artistic mind. Successive generations of painters have handed on the traditions of these early workers, and in this respect, at any rate, have acquired popularity in proportion to their fidelity to these original ideals.

Angel of the Resurrection by F. J. Williamson

In Memoriam by F. J. Williamson

A word or two remains to he said concerning sculptured angels, of which four examples are illustrated. The sculptor is, of course, more heavily handicapped by his material than his painter-brother. It is impossible to suggest spirituality of being in marble or bronze. All that can be done is to bestow as much grace and beauty on the figure as is possible. That Mr. F. J. Williamson, the genial sculptor to the Queen, has done this in the examples given of his work on pages 772 and 777 need hardly to be pointed out. So far as success can be achieved in this direction it is his.

Angels from Viscount Melbourne’s Monument, St. Paul’s Cathedral by Baron Marochetti

The examples of sculptured angels on page 773 are from the well-known monument to Viscount Melbourne, the Queen’s first Prime Minister, in the north aisle of St. Paul’s Cathedral. On either side of the great black marble gates stands the figure of a sleeping angel, one with a sword and the other with a trumpet. The monument was the work of Baron Marochetti, and while it forms an imposing feature of the great cathedral, it must be confessed that it is grandiose rather than dignified.

Though it cannot properly be included in this paper dealing with the work of modern artists, I cannot refrain from mentioning, in connection with sculptured angels, the curious representation of Jacob’s ladder to be seen on the front of the Abbey Church at Bath. On either side of the main doorway the ladder stretches up the noble front of the building, the angels ascending on one side and descending on the other, and although many of the figures are broken or worn away by the action of the weather, the whole forms an interesting example of the work under notice.

That these two articles do not pretend to deal with the subject exhaustively is obvious—space would not allow more than a mere outline but sufficient has been said to show its possibilities and the fascinating interest of its study.

Source: Fish, Arthur. “Picturing the Angels.” The Quiver. London: Cassell & Company, Ltd., 1897.

Please visit Christian Image Source to download free Angel Drawings.

By Karen, on September 10th, 2010

Guardian Angels Guardian Angels

At the close of the previous article [Angel Art – Part 2] I ventured to express the opinion that we should find the most successful modern artists who have pictured the angelic form to be those who have worked in the same simple spiritual manner as did the Pre-Raphaelite Italian painters. The religious ideal in art has been seldom attained: it demands something more than mere technical skill: the quietude of life, the purity of thought, the calm faith which Fra Angelico cultivated, are needed to produce the proper state of mind to direct the physical power of the work. There have been many modern painters who have set themselves to paint religious pictures, but those to whom success can be attributed are few.

Some there are who condemn the effort to delineate the physically unseen. Materialists themselves, they deny the right to others of finer susceptibilities to see visions and dream dreams. The imaginative faculty, however, properly exercised and controlled, combined with due facility of expression, is capable of doing great things in art; and in no direction can this faculty have greater play, or demand greater technical skill, than in the picturing of angels.

Mr. Ruskin treats fully of this matter in one of the chapters of “Modern Painters,” and the following passage dealing with this point is of great interest:—

“There is one true form of religious art, nevertheless, in the pictures of the passionate ideal which represent imaginary beings of another world. Since it is evidently right that we should try to imagine the glories of the next world, and as this imagination must be, in each separate mind, more or less different, and unconfined by any laws of material fact, the passionate ideal has not only full scope here, but it becomes our duty to urge its powers to its utmost, so that every condition of beautiful form and colour may he employed to invest these scenes with greater delightfulness (the whole being, of course, received as an assertion of possibility, not of absolute fact). All the paradises imagined by the religious painters— the choirs of glorified saints, angels, and spiritual powers, when painted with the full belief in this possibility of their existence, are true ideals: and so far from our having dwelt on these too much, I believe, rather, we have not trusted them enough, nor accepted them enough, as possible statements of most precious truths. Nothing but unmixed good can accrue, to my mind, from the contemplation of the scenes laid in Heaven by faithful religious masters: and the more they are considered, not as works of art, but as real visions of real things, more or less imperfectly set down, the more good will be got by dwelling upon them.”

Modern pictorial angels have, of course, for the most part figured in illustrations of Bible stories, and, as a rule, have been drawn strictly on conventional lines, and on this account, therefore, I shall omit references to many artists, reserving the greater space for those who demand it by their greater imaginative faculty.

Satan in his Original Glory by William Blake

To many, doubtless, the name of William Blake is familiar; but few are acquainted with the curious temperament and character of the man. His work, too, is probably unknown to many, but those who saw a collection of his drawings at the winter exhibition of the Royal Academy a few years ago must have been struck with the curious originality, amounting almost to eccentricity, of his illustrations of Bible incidents. He was a man distinctly in advance of his times—he lived towards the close of the last century—and was possessed of a mind always dwelling upon the mysteries of the unseen. When but eight years of age he declared that he saw angels in the trees on Peckham Rye, thereby incurring his father’s displeasure to the extent of a threatened flogging, and in his after-life his imagination ran far ahead of the powers of his pencil. But he believed firmly in his visions, and religious faith was the foundation of his life. On one occasion a young artist complained to him that at times his inventive faculties appeared to vanish.

“It is just so with us, is it not,” replied Blake, turning to his wife, “for weeks together, when the visions forsake us? What do we do then, Kate?”

“We kneel down and pray.”

And judging his work in the light of this fact, we have to acknowledge it was honest and conscientious—the outcome of his heartfelt convictions. Blake’s angels are unique in their unconventionality: they suggest the strength and majesty of the heavenly messengers rather than their beauty.

Archangel Gabriel in The Annunciation by Dante Gabriel Rossetti Archangel Gabriel in The Annunciation by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

A great admirer of Blake’s work was Dante Gabriel Rossetti, one of the most original painters of recent years. The special work by him, which calls for attention here, is The Annunciation in the National Gallery. This charming water-colour drawing is undoubtedly one of the most precious gems in the collection, and to those unfamiliar with it a visit to the Gallery should become a necessity. The figure of the angel is beautiful and imposing, and the whole composition tenderly reverent. Rossetti discarded the conventional wings at the shoulders of the angel, bestowing instead wings of flame on the feet. Clothed in a long blue robe, in his right hand a branch of lily blossom, Gabriel stands delivering his message to Mary.

Alleluia by Sir Edward Burne-Jones

From Rossetti the mind turns naturally to Sir Edward Burne-Jones, his companion and co-worker. It has fallen to him above all others to carry on the tradition associated with Rossetti’s work, whilst retaining to the full his own originality of conception and execution. Working apart from all academic associations, he “has steadfastly” gone his own way, uninfluenced by criticism, either hostile or favourable; he has conquered prejudice, and wrung recognition of his talents from all quarters. Never seeking preferment or honour, they have been bestowed upon him in spite of himself. And in all he has retained his independence of spirit, resigning the grudgingly bestowed Associateship of the Royal Academy rather than sacrifice it. Then came the royal conferment of a baronetcy, of which today he is the sole artistic possessor.

The two works of his which we reproduce are typical of his art. Truly religious in artistic feeling, his greatest powers have been bestowed upon schemes of decoration for ecclesiastical purposes, and his lifelong companionship with the late William Morris gave him full opportunity for their display. The illustration on page 772 represents one of a series of figures of angels executed in mosaics, forming part of the decoration of the American Church in Rome. The large figure of an angel shown on page 776 [shown above] is taken from the wonderful tapestry in the chapel of Exeter College, Oxford, illustrating the visit of the wise men to the infant Christ.

The beauty of the many windows designed by Sir Edward Burne-Jones, and placed in churches in various parts of the country, places him in the front rank of designers of such work. One of the finest examples is to be seen in Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Street, London.

Angel from St. Paul’s Cathedral, London Angel from St. Paul’s Cathedral, London

The mention of this affords opportunity for referring to the commendable growing practice of beautifying our places of worship. One of the most notable instances is, of course, St. Paul’s Cathedral, upon which Mr. W. B. Richmond, R.A., has been engaged so long and so successfully. The now completed choir testifies to the patient skill of the artist, and the harmonious splendour of the work will justify the placing of his name on the same enduring roll of fame which contains that of the great architect of the building. Angels figure largely in Mr. Richmond’s scheme of design, and are of great beauty. As the choir is now thrown open to the public, an opportunity is afforded of getting within reasonable distance to see the work.

A Spandrel in the Dome of St. Paul’s

We also reproduce on page 778 one of the designs from the spandrels under the dome of the cathedral, designed by that other noble artist. Mr. G. F. Watts R.A. He, too, always works at his art for art’s sake. Disregarding popularity, he steadily follows his heart’s biddings in his work. With opportunities for acquiring great wealth by his painting, he has put them aside, and generously given the best of his life’s work to the nation.

Source: Fish, Arthur. “Picturing the Angels.” The Quiver. London: Cassell & Company, Ltd., 1897.

Be sure to visit Christian Image Source for Free Angel Graphics.

By Karen, on August 22nd, 2010

Heavenly Angels

Bearing these remarks in mind, [Angel Art: Part 1] let us examine the pictorial representations of angels by the early masters in art. It is necessary, too, to remember that Christian art at the first was directed and controlled by the Church. Art was bound to the service of religion: all its life and force were expended upon it, and, indeed, the workers themselves were, for the most part, until the thirteenth century, of the Church. We cannot touch upon the crude productions of the very early artists, and can only barely refer to the culmination of their art as exhibited in illuminated manuscripts. The beauty and delicacy of these decorated parchments are wonderful. With the use of the primary colours and gold, these, to us nameless, workers produced miniature pictures the charm of which—more than six centuries after their creators have passed away—still enthralls us.

Madonna and Child by Cimabue

It is not until we come to the thirteenth century that we can identify any particular artist with his work; and in our National Gallery is to be seen a painting by Margaritone, dating from this period, which shows us exactly how far art had progressed, and, as it contains representations of angels, is of interest to us. It is ugly and crude; the figures are lifeless, stiff, and, judged by our canons of art, absurd; but the angels show that even then the conventional form of heavenly beings was accepted. Before Margaritone died, Cimabue and his talented pupil Giotto had become known. Their work marks the first real step in the advance of art. We have one of Cimabue’s works in the National Gallery—and, for convenience sake, reference will be chiefly made in this article to pictures in that collection. It is, of course, a painting of the Madonna and Child, and on either side of these figures are three half-length representations of angels—beautiful female faces, with heavily gilt halos behind, and hands clasped in adoration.

Angels Adoring by Orcagna

In a picture marked of “The School of Giotto” there are also angelic figures; but passing to our first illustration—a group of angels by Orcagna (1329-1376?)—we shall find a great advance has been made. Although the influence of the illuminator still lingers in the colouring, we have now a suggestion of movement in the figures. Designed as one wing of a triptych, decoration was the main object of the artist. The angels are clad in robes of white, red, blue, and green, and are both male and female with halos of gold, richly decorated.

Angel Art by Fra Angelico

But the most refined, the most skillful, the most religious, of the fourteenth-century painters was Fra Angelico, the Dominican monk. Entering the convent at Fiesole when about twenty-one years of age, his work was carried out under the spell of the Church and in the quietude of a devotional life, and it all reflects the steadfast faith and purity of soul of the artist. Old Vasari says of him:—“He laboured continually at his paintings, but would do nothing that was not connected with things holy. . . . He used frequently to say that he who practised the art of painting had need of quiet, and should live without taking thought, adding that he who does Christ’s work should always live with Christ. It is also affirmed that he would never take a pencil in his hand until he had first offered a prayer.”

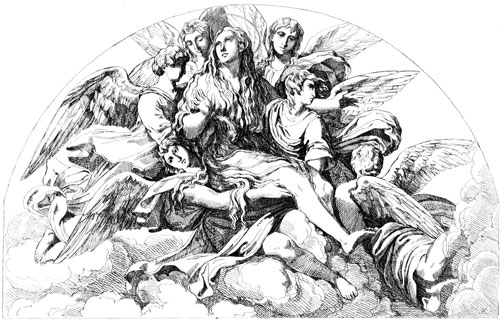

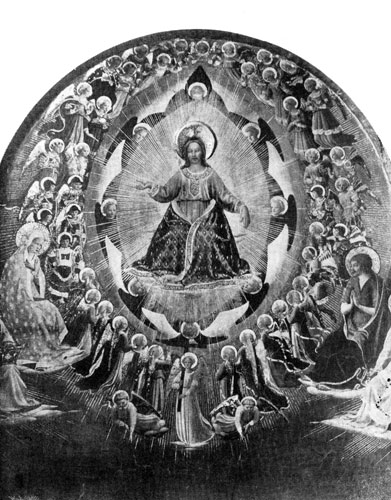

The picture by him at the National Gallery, “Christ with the Banner of the Redemption” (No. 663), contains over two hundred figures, and among them a large group of angels, the beauty of whose forms and countenances has never been equalled. He was the ideal painter of the celestial choirs, infusing into his work the enthusiasm of a holy joy in beauty and spirituality.

from The Annunciation by Fra Angelico

Mr. Ruskin writes of Fra Angelico and his angels: “By purity of life, habitual elevation of thought, and natural sweetness of disposition, he was enabled to express the sacred affections upon the human countenance as no one ever did before or since. In order to effect clearer distinction between heavenly beings and those of this world, he represents the former as clothed in draperies of the purest colour, crowned with glories of burnished gold, and entirely shadowless. With exquisite choice of gesture, and disposition of folds of drapery, his mode of treatment gives perhaps the best idea of spiritual beings which the human mind is capable of forming. With what comparison shall we compare the angel choirs of Angelico, with the flames on their white foreheads waving together as they move, and the sparkles streaming from their purple wings like the glitter of many suns upon a sounding sea, listening in the pauses of eternal song for the prolonging of the trumpet-blast and the answering of psaltery and cymbal, throughout the endless deep and from all the star shores of Heaven?”

Angels by Van Eyck

It is curious to turn from these spiritual creations of the Italian monk to the work of a contemporary in another country—Jan van Eyck, the Flemish master. It is difficult to imagine they were contemporary when we look at their work. These Flemish angels are so mundane, the Florentine so ethereal: the one so human, the others so sweet and soulful.

Annunciation by Fra Lippo Lippi

Returning to Italy, we find in the fifteenth century that artists, while still chiefly devoting their attention to religious subjects, have learned more of the technique of their art. They had begun to study Nature, and to use objects about them for their models. Fra Lippo Lippi painted some sweet faces in his angelic representations, but they are not spiritual, being obviously modelled from people of his time. His angel in “The Annunciation,” in the National Gallery, is a Florentine boy—very beautiful, but still human. His dress is a wonderful piece of workmanship, the wings are marvellously executed, evidently based upon the form of the peacock’s. It is curious to note, too, that he suggests the connection of these with the body for the first time, so far as I can trace; for the angel has an epaulette arrangement of feathers on the shoulder. Fra Filippo’s son, Filippino Lippi, too, was, a fine painter; but the angel of his, which we reproduce, approaches still nearer the merely human.

The Nativity by Botticelli

We come now to one of the greatest painters of the period — Sandro Filipepi, generally known as Botticelli, an artist of lively imagination. His angels, which may be seen in two of his best works—fortunately in our gallery — “The Nativity” and “The Assumption of the Virgin,” are quite different from all those of his predecessors. In the former—painted when the artist was under the spell of Savonarola—the angels are in a frenzy of enthusiasm. They carry palms and crowns as they float round in a circle over the stable containing the newborn Redeemer, and in the foreground of the picture embrace each other ecstatically in the fervour of their joy.

A Chorus of Angels by Simon Marmion

Angel by Fra Bartolommeo

Angel from The Presentation in the Temple by Carpaccio

Our illustrations on this page and the preceding date from the fifteenth century. That by Simon Marmion, a French painter (No. 1303 in the National Gallery), is curious from the fact that the artist has evaded the necessity of painting the lower limbs by the arrangement of his drapery; and all three markedly show the difference between the work of Fra Angelico and that of his successors. Fra Bartolommeo’s is an example of the “cherub” type, which was replacing that of former years; while Carpaccio’s still retains some of the beauty without any of the spirituality of his predecessor’s.

Assumption by Matteo Giovanni

Nativity by Piero della Francesca

Of the numerous other artists of the Italian school, space will not allow us to speak: we can only draw attention to their works in the National Gallery. By Matteo Giovanni there are some beautifully idealised children, who serve as angels in his “Assumption” (No. 1155); and in a “Holy Family,” by Ludovico Mazzolini, there is a charming group of angelic beings playing upon harps and an organ. The angels of Piero della Francesca in his “Nativity” are exceedingly unconventional, being wingless as well as haloless. They are simply beautiful Italian peasant-girls playing upon mandolines.

Francia’s wonderful picture of “The Virgin and Angels Weeping over the Dead Body of Christ” contains two angels of surpassing beauty: one robed in green, and the other in red. No. 781—a painting of “The Angel Raphael accompanying Tobias”—is remarkable for the skill and beauty of the wings. By Perugino (Raphael’s master) there is only one example with the angels; and they are but decorative adjuncts to the principal figures; and there is but one by Michael Angelo (No. 809), an unfinished work.

Tobias and the Angel by Elseheimer

The example of German art, which we give, can also be seen in the National Gallery. It dates from the sixteenth century, and serves to show the “fleshly” style, of the Northern art. The angel is of the same type as Tobias, who is merely a German peasant of the day. Never again did the angel in art attain the glory of the fourteenth century.

Assumption of the Virgin by Valdes Leal

The Spanish school made him merely a chubby boy—which can be typified in Valdes Leal’s “Assumption of the Virgin” at the National Gallery (No. 1291). The painters seem barely to recognise the difference between Cupids and cherubs; indeed, Poussin, the Frenchman, made no difference whatever. We shall consider in a subsequent article the treatment of the subject by modern painters, and shall find that the most successful of them have gone back to the spirit of the pre-Raphaelite artists.

Source: Fish, Arthur. “Picturing the Angels.” The Quiver. London: Cassell & Company, Ltd., 1897.

Be sure to visit Christian Image Source for free Angel Graphics.

|

|

|

Angel Graphics

Angel Graphics

Pictures of Angels

Pictures of Angels

Archangels: Part 1

Archangels

There are several angels who in artistic representations have assumed an individual form and character. These belong to the order of Archangels, placed by Dionysius in the third Hierarchy: they take rank between the Princedoms and the Angels and partake of the nature of both. Like the Princedoms, they have Powers; and, like the Angels, they are Ministers and Messengers.

Frequent allusion is made in Scripture to the seven Angels who stand in the presence of God. (Rev. viii. 2, xv. 1, xvi. 1, etc.; Tobit xxii. 15.) This was in accordance with the popular creed of the Jews, who not only acknowledged the supremacy of the Seven Spirits, but assigned to them distinct vocations and distinct appellations, each terminating with the syllable El, which signifies God. Thus we have —

I. Michael (i. e. who is like unto God), captain-general of the host of heaven, and protector of the Hebrew nation.

II. Gabriel (i. e. God is my strength), guardian of the celestial treasury, and preceptor of the patriarch Joseph.

III. Raphael (i. e. the Medicine of God), the conductor of Tobit; thence the chief guardian angel.

IV. Uriel (i. e. the Light of God), who taught Esdras. He was also regent of the sun.

V. Chamuel (i. e. one who sees God), who wrestled with Jacob, and who appeared to Christ at Gethsemane. (However, according to other authorities, this was the angel Gabriel.)

VI. Jophiel (i. e. the Beauty of God), who was the preceptor of the sons of Noah, and is the protector of all those who, with a humble heart, seek after truth, and the enemy of those who pursue vain knowledge. Thus Jophiel was naturally considered as the guardian of the tree of knowledge, and the same who drove Adam and Eve from Paradise.

VII. Zadkiel (i. e. the Righteousness of God), who stayed the hand of Abraham when about to sacrifice his son. (But, according to other authorities, this was the archangel Michael.)

The Christian Church does not acknowledge these Seven Angels by name, neither in the East, where the worship of angels took deep root, nor yet in the West, where it has been tacitly accepted. Nor have they been met as a series, by name, in any ecclesiastical work of Art, though there is a set of old anonymous prints in which they appear with distinct names and attributes: Michael bears the sword and scales; Gabriel, the lily; Raphael, the pilgrim’s staff and gourd full of water, as a traveler. Uriel has a roll and a book: he is the interpreter of judgments and prophecies, and for this purpose was sent to Esdras.”The angel that was sent unto me, whose name was Uriel, gave me an answer.” (Esdras ii. 4.)

And in Milton —,

According to an early Christian tradition, it was this angel, and not Christ in person, who accompanied the two disciples to Emmaus. Chanmel is represented with a cup and a staff; Jophiel with a flaming sword. Zadkiel bears the sacrificial knife which he took from the hand of Abraham.

But the Seven Angels, without being distinguished by name, are occasionally introduced into works of art. For example, over the arch of the choir in San Michele, at Ravenna (A. D. 545), on each side of the throned Saviour are the Seven Angels blowing trumpets like cow’s horns: “And I saw the Seven Angels which stand before God, and to them were given seven trumpets.” (Rev. viii. 2, 6.) In representations of the Crucifixion and in the Pieta, the Seven Angels are often seen in attendance, bearing the instruments of the Passion. Michael bears the cross, for he is “the Bannerer of heaven,” but the particular avocations of the others is uncertain.

In the Last Judgment of Orcagna, in the Campo Santo at Pisa, the Seven Angels are active and important personages. The angel who stands in the center of the picture, below the throne of Christ, extends a scroll in each hand. On the scroll in the right hand is inscribed, “Come, ye blessed of my Father,” and on the scroll in the left hand, “Depart from me, ye accursed.” The angel is supposed to be Michael, the angel of judgment. At his feet crouches an angel, who seems to shrink from the tremendous spectacle, and hides his face. This angel is supposed to be Raphael, the guardian angel of humanity. The attitude has always been admired — cowering with horror, yet sublime. Beneath are another five angels, who are engaged in separating the just from the wicked, encouraging and sustaining the former, and driving the latter towards the demons who are ready to snatch them into flames. These Seven Angels have the garb of princes and warriors, with breastplates of gold, jeweled sword belts and tiaras, and rich mantles; while the other angels who figure in the same scene are plumed and bird-like, and hover above, bearing the instruments of the Passion.

Again we may see the Seven Angels in quite another character, attending on St. Thomas Aquinas, in a picture by Taddeo Gaddi. Here, instead of the instruments of the Passion, they bear the allegorical attributes of those virtues for which that famous saint and doctor is to be reverenced. One bears an olive-branch, i. e. Peace. The second holds a book, i. e. Knowledge. The third, a crown and sceptre, i. e. Power. The fourth holds a replica of a church, i. e. Religion. The fifth holds a cross and shield, i. e. Faith. The sixth holds flames of fire in each hand, i.e. Piety and Charity. Finally, the seventh angel holds a lily, i. e. Purity.

In general it may be presumed that when seven angels figure together, or are distinguished from among a host of angels by dress, stature, or other attributes, that these represent “the Seven Holy Angels who stand in the presence of God.” Four only of these Seven Angels are individualized by name: Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, and Uriel. According to the Jewish tradition, these four sustain the throne of the Almighty; they have the Greek epithet arch, or chief, assigned to them, from the two texts of Scripture in which that title is used (1 Thess. iv. 16 ; Jude 9), but only the three first, who in Scripture have a distinct personality, are reverenced in the Catholic Church as saints, and their gracious beauty, divine prowess, and high behests to mortal man have furnished some of the most important and most poetical subjects which appear in Christian Art.

Source: Jameson, Anna. Sacred and Legendary Art – Volume 1. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longman’s & Roberts, 1987.