Bearing these remarks in mind, [Angel Art: Part 1] let us examine the pictorial representations of angels by the early masters in art. It is necessary, too, to remember that Christian art at the first was directed and controlled by the Church. Art was bound to the service of religion: all its life and force were expended upon it, and, indeed, the workers themselves were, for the most part, until the thirteenth century, of the Church. We cannot touch upon the crude productions of the very early artists, and can only barely refer to the culmination of their art as exhibited in illuminated manuscripts. The beauty and delicacy of these decorated parchments are wonderful. With the use of the primary colours and gold, these, to us nameless, workers produced miniature pictures the charm of which—more than six centuries after their creators have passed away—still enthralls us.

Madonna and Child by Cimabue

It is not until we come to the thirteenth century that we can identify any particular artist with his work; and in our National Gallery is to be seen a painting by Margaritone, dating from this period, which shows us exactly how far art had progressed, and, as it contains representations of angels, is of interest to us. It is ugly and crude; the figures are lifeless, stiff, and, judged by our canons of art, absurd; but the angels show that even then the conventional form of heavenly beings was accepted. Before Margaritone died, Cimabue and his talented pupil Giotto had become known. Their work marks the first real step in the advance of art. We have one of Cimabue’s works in the National Gallery—and, for convenience sake, reference will be chiefly made in this article to pictures in that collection. It is, of course, a painting of the Madonna and Child, and on either side of these figures are three half-length representations of angels—beautiful female faces, with heavily gilt halos behind, and hands clasped in adoration.

Angels Adoring by Orcagna

In a picture marked of “The School of Giotto” there are also angelic figures; but passing to our first illustration—a group of angels by Orcagna (1329-1376?)—we shall find a great advance has been made. Although the influence of the illuminator still lingers in the colouring, we have now a suggestion of movement in the figures. Designed as one wing of a triptych, decoration was the main object of the artist. The angels are clad in robes of white, red, blue, and green, and are both male and female with halos of gold, richly decorated.

Angel Art by Fra Angelico

But the most refined, the most skillful, the most religious, of the fourteenth-century painters was Fra Angelico, the Dominican monk. Entering the convent at Fiesole when about twenty-one years of age, his work was carried out under the spell of the Church and in the quietude of a devotional life, and it all reflects the steadfast faith and purity of soul of the artist. Old Vasari says of him:—“He laboured continually at his paintings, but would do nothing that was not connected with things holy. . . . He used frequently to say that he who practised the art of painting had need of quiet, and should live without taking thought, adding that he who does Christ’s work should always live with Christ. It is also affirmed that he would never take a pencil in his hand until he had first offered a prayer.”

The picture by him at the National Gallery, “Christ with the Banner of the Redemption” (No. 663), contains over two hundred figures, and among them a large group of angels, the beauty of whose forms and countenances has never been equalled. He was the ideal painter of the celestial choirs, infusing into his work the enthusiasm of a holy joy in beauty and spirituality.

from The Annunciation by Fra Angelico

Mr. Ruskin writes of Fra Angelico and his angels: “By purity of life, habitual elevation of thought, and natural sweetness of disposition, he was enabled to express the sacred affections upon the human countenance as no one ever did before or since. In order to effect clearer distinction between heavenly beings and those of this world, he represents the former as clothed in draperies of the purest colour, crowned with glories of burnished gold, and entirely shadowless. With exquisite choice of gesture, and disposition of folds of drapery, his mode of treatment gives perhaps the best idea of spiritual beings which the human mind is capable of forming. With what comparison shall we compare the angel choirs of Angelico, with the flames on their white foreheads waving together as they move, and the sparkles streaming from their purple wings like the glitter of many suns upon a sounding sea, listening in the pauses of eternal song for the prolonging of the trumpet-blast and the answering of psaltery and cymbal, throughout the endless deep and from all the star shores of Heaven?”

Angels by Van Eyck

It is curious to turn from these spiritual creations of the Italian monk to the work of a contemporary in another country—Jan van Eyck, the Flemish master. It is difficult to imagine they were contemporary when we look at their work. These Flemish angels are so mundane, the Florentine so ethereal: the one so human, the others so sweet and soulful.

Annunciation by Fra Lippo Lippi

Returning to Italy, we find in the fifteenth century that artists, while still chiefly devoting their attention to religious subjects, have learned more of the technique of their art. They had begun to study Nature, and to use objects about them for their models. Fra Lippo Lippi painted some sweet faces in his angelic representations, but they are not spiritual, being obviously modelled from people of his time. His angel in “The Annunciation,” in the National Gallery, is a Florentine boy—very beautiful, but still human. His dress is a wonderful piece of workmanship, the wings are marvellously executed, evidently based upon the form of the peacock’s. It is curious to note, too, that he suggests the connection of these with the body for the first time, so far as I can trace; for the angel has an epaulette arrangement of feathers on the shoulder. Fra Filippo’s son, Filippino Lippi, too, was, a fine painter; but the angel of his, which we reproduce, approaches still nearer the merely human.

The Nativity by Botticelli

We come now to one of the greatest painters of the period — Sandro Filipepi, generally known as Botticelli, an artist of lively imagination. His angels, which may be seen in two of his best works—fortunately in our gallery — “The Nativity” and “The Assumption of the Virgin,” are quite different from all those of his predecessors. In the former—painted when the artist was under the spell of Savonarola—the angels are in a frenzy of enthusiasm. They carry palms and crowns as they float round in a circle over the stable containing the newborn Redeemer, and in the foreground of the picture embrace each other ecstatically in the fervour of their joy.

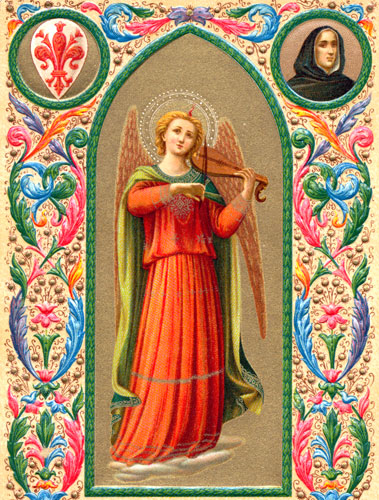

A Chorus of Angels by Simon Marmion

Angel by Fra Bartolommeo

Angel from The Presentation in the Temple by Carpaccio

Our illustrations on this page and the preceding date from the fifteenth century. That by Simon Marmion, a French painter (No. 1303 in the National Gallery), is curious from the fact that the artist has evaded the necessity of painting the lower limbs by the arrangement of his drapery; and all three markedly show the difference between the work of Fra Angelico and that of his successors. Fra Bartolommeo’s is an example of the “cherub” type, which was replacing that of former years; while Carpaccio’s still retains some of the beauty without any of the spirituality of his predecessor’s.

Assumption by Matteo Giovanni

Nativity by Piero della Francesca

Of the numerous other artists of the Italian school, space will not allow us to speak: we can only draw attention to their works in the National Gallery. By Matteo Giovanni there are some beautifully idealised children, who serve as angels in his “Assumption” (No. 1155); and in a “Holy Family,” by Ludovico Mazzolini, there is a charming group of angelic beings playing upon harps and an organ. The angels of Piero della Francesca in his “Nativity” are exceedingly unconventional, being wingless as well as haloless. They are simply beautiful Italian peasant-girls playing upon mandolines.

Francia’s wonderful picture of “The Virgin and Angels Weeping over the Dead Body of Christ” contains two angels of surpassing beauty: one robed in green, and the other in red. No. 781—a painting of “The Angel Raphael accompanying Tobias”—is remarkable for the skill and beauty of the wings. By Perugino (Raphael’s master) there is only one example with the angels; and they are but decorative adjuncts to the principal figures; and there is but one by Michael Angelo (No. 809), an unfinished work.

Tobias and the Angel by Elseheimer

The example of German art, which we give, can also be seen in the National Gallery. It dates from the sixteenth century, and serves to show the “fleshly” style, of the Northern art. The angel is of the same type as Tobias, who is merely a German peasant of the day. Never again did the angel in art attain the glory of the fourteenth century.

Assumption of the Virgin by Valdes Leal

The Spanish school made him merely a chubby boy—which can be typified in Valdes Leal’s “Assumption of the Virgin” at the National Gallery (No. 1291). The painters seem barely to recognise the difference between Cupids and cherubs; indeed, Poussin, the Frenchman, made no difference whatever. We shall consider in a subsequent article the treatment of the subject by modern painters, and shall find that the most successful of them have gone back to the spirit of the pre-Raphaelite artists.

Source: Fish, Arthur. “Picturing the Angels.” The Quiver. London: Cassell & Company, Ltd., 1897.

Be sure to visit Christian Image Source for free Angel Graphics.